Discover The Story

Fighting on the Border

The heated words and actions of early 1861 turned into bullets and cannon balls on April 12 when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter. Mid-Maryland and the Virginia countryside bordering the Potomac River were quickly transformed into a war zone as both sides recognized the strategic military significance of the invisible dividing line.

For the next four years, this border region from south-central Pennsylvania through mid-Maryland and into Virginia was the scene of some of the most important military battles in American history. Antietam, Gettysburg, Monocacy, and many smaller engagements helped determine the outcome of the Civil War and the fate of the United States.

Opening Salvos

Before the war commenced, there had been fiery debate throughout the region on the legality of secession, slavery, the sanctity of the Union versus the rights of states, and last-minute compromises. Once fighting began, however, choices became clearer and sides were chosen. Pennsylvania quickly pledged allegiance to the Union, and Virginia likewise to the Confederacy. There were opposing voices in both states, but they were quickly silenced by the ardent war spirit of the majority. Citizens in Maryland were more conflicted. As a border slave state, Maryland had ties to both the North and the South. Baltimore and southern Maryland were generally more sympathetic with the South, and the mid-Maryland region more with the Union, but loyalties were strained throughout the state.

In Maryland there were conflicting opinions about the propriety of calling out the General Assembly, which met biannually and was not scheduled to meet again until 1862. Throughout the “Secession Winter” of 1860-61, Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks had resisted pressure, primarily from Southern Rights supporters, to convene the body. Only after secession sympathizers in Baltimore had attacked troops passing through the city on their way to defend Washington, D.C. on April 19 – known as the “Pratt Street Riot” – and had begun organizing an extralegal meeting of the legislature did Hicks relent. The governor called the General Assembly to meet in Frederick, however, which had stronger Union sentiment than existed in the state capital at Annapolis.

The divided sentiment in the state was reflected to some degree in Frederick as well. When the legislators arrived in Frederick on April 26, they discovered that loyal state militia, supplemented by a local home guard force, was patrolling the streets. Not everyone from Frederick was happy that Unionists controlled the city. A pro-South newspaper from Frederick wrote: “In would appear that a quasi-system of surveillance exists in our midst. . . . It is well known that several quiet, order-loving and unoffending citizens had been forced at the point of a bayonet to stand and submit to the indignity of being questioned, and perchance insulted by irresponsible persons, who believe themselves clothed with a little brief authority.”

Ultimately, the General Assembly adjourned its first session on May 14 without taking any steps that might lead toward secession. The legislators declared that it was “inexpedient” to convene a sovereign convention that might consider secession or to reorganize the state militia. Some believed that the local militia had intimidated the legislature. John A. Steiner, a member of the Home Guard, later wrote: “It was generally believed then that the firm and decided action of the Frederick City Home Guards held the Legislature of Maryland in check, so that no positive disloyal legislation was had.” The General Assembly met two more times in Frederick over the summer, but the arrest of pro-Southern legislators in September, ordered by Federal authorities, ended any possibility the state would secede.

On the military front, before the Maryland General Assembly even had a chance to meet, Confederate forces occupied Harpers Ferry, Virginia, on April 17 and extended pickets along the Potomac River. Colonel Thomas J. Jackson commanded the post for about a month, followed by General Joseph E. Johnston. The first Confederate occupation of Maryland soil occurred during this time when southern troops were sent to Maryland Heights, the mountainous high ground that overlooked Harpers Ferry from the north. Southern troops were also posted in Maryland along the towpath of the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal, where sentinels required boat captains to obtain passes from the Confederates before they would allow them to proceed. The Confederates also occupied the Maryland side of the turnpike bridge at Point of Rocks and stopped trains on the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad. On April 24 troops from Virginia crossed into Maryland and seized two canal boats loaded with grain at Berlin (present-day Brunswick). In Washington County, numerous skirmishes broke out between the Confederates and local home guard companies from Clear Spring, Williamsport, and Sharpsburg.

In response to the Confederate threat in the lower Shenandoah Valley, in the spring of 1861 a Union army was formed at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania under the command of Major General Robert Patterson, who planned a movement against Harpers Ferry. By early June his army numbered over 10,000 men. On June 15 Patterson headed south into Washington County, Maryland. Camps were established at various locales in and around Hagerstown, Funkstown, and Williamsport. Local Unionists were happy to hear of Patterson’s advance. A Berlin resident wrote optimistically: “I can say that our District will welcome the Federal troops with a great deal of hospitality when they arrive, and indeed many are impatient to see them on our railroad and canal, as the two great works are to be resumed very soon, and business will flourish as formerly.”

In the face of Patterson’s advance into Maryland, Johnston evacuated Harpers Ferry. Before leaving, his men disabled the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the C&O Canal. These transportation lines were important to the local economy and to the U.S. government, especially for the transportation of coal and flour. One local resident wrote that the damage inflicted on the canal by the Confederates “has done more for the Union sentiment in this quarter than any other act that has transpired thus far.”

On July 2, Patterson crossed the Potomac at Williamsport. After a few miles, the Union invaders clashed with part of Johnston’s army under Jackson at the Battle of Falling Waters. In the only sizable action in this campaign, the Union side suffered more losses, but Jackson left Patterson in possession of the battlefield.

On July 2, Patterson crossed the Potomac at Williamsport. After a few miles, the Union invaders clashed with part of Johnston’s army under Jackson at the Battle of Falling Waters. In the only sizable action in this campaign, the Union side suffered more losses, but Jackson left Patterson in possession of the battlefield.

Patterson led his army to Martinsburg, where on July 8 he was joined by a column of 2,000 troops led by Colonel Charles P. Stone. Stone’s Rockville Expedition had departed Washington a month earlier and placed the first U.S. pickets along the Potomac River above Washington before he was ordered to join Patterson.

Meanwhile, a sizable Confederate force was gathering at Manassas Junction, Virginia, about twenty miles southwest of Washington, D.C., under Brigadier General Pierre G.T. Beauregard. A nervous President Abraham Lincoln pressed his military commanders to take action. Accordingly, Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, newly appointed commander of the Department of Northeastern Virginia, hastily prepared his army to strike Beauregard’s forces.

With Harpers Ferry evacuated, Patterson was directed to prevent Johnston from reinforcing Beauregard at Manassas. Instead of pursuing Johnston at Winchester, Virginia, however, he became indecisive. This gave Johnston the opportunity he needed to slip away. Johnston later gave much credit to his cavalry officer, James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart: “Although the Federal cavalry had greatly the advantage of the Confederate in arms and discipline, it was not in the habit, like ours, of leaving the protection of the infantry. This enabled Stuart to maintain his outposts near the enemy’s camps, and his scouts near their columns, learning their movements quickly, and concealing our own.” On July 17 Johnston’s men marched to Piedmont and boarded trains for Manassas, which strengthened Beauregard and helped lead to the defeat of McDowell at the Battle of First Bull Run (or First Manassas).

During the summer of 1861, the Confederates constructed a series of forts around Manassas Junction and in Fairfax and Loudoun Counties. Among them was Fort Evans, near Leesburg. The presence of Confederate forces so close to Washington worried Lincoln. That fall Major General George B. McClellan, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, directed a series of movements to maneuver the Confederates out of northern Virginia.

McClellan directed new Brigadier General Charles P. Stone, who commanded a division at Poolesville, Maryland, to mount a “slight demonstration” that might force the Confederate brigade of Colonel Nathan Evans out of Leesburg. On October 21, 1861 Stone sent a brigade commanded by Colonel Edward Baker, a sitting U.S. Senator and close friend of Lincoln, across the Potomac and up Ball’s Bluff. Baker’s men scaled the seventy-foot heights and proceeded with neither the proper reconnaissancenor enough boats to facilitate a safe withdrawal back to Maryland if needed. On the day of the battle Stone informed McClellan: “We are a little short of boats,” which was symbolic of the lack of foresight and preparation that preceded the engagement. In the debacle that followed, Baker’s brigade was outflanked by Evan’s Confederate force. Baker was killed, and in the Union retreat many soldiers were drowned as they attempted to cross the river. Many of the bodies floated downstream past Washington, exacerbating civilian anxiety in the nation’s capital. Although a relatively small battle, the losses at Balls Bluff had a tremendous psychological impact on the North.

As the year ended, there was little “quiet along the Potomac.” Between the second week of December and the first few days of January 1862, Confederates forces from Jackson’s Valley District made three separate raids against Dam Number 5 on the Potomac above Williamsport, and one against Dam Number 4 below the town. Jackson had hoped that the destruction of the dams would disable the C&O Canal, on which navigation had resumed in August. The river was heavily guarded by Union forces, however, and ultimately all of Jackson’s attempts were unsuccessful.

The Maryland Campaign of 1862

In early 1862, despite harsh winter weather, Jackson began a new campaign at Romney, Virginia. On January 4 he drove the Federals out of Bath (Berkeley Springs), Virginia, pursuing them to the Potomac River at Hancock, Maryland, where he threatened to bombard the town if it did not surrender. Union Brigadier General Frederick W. Lander replied to the messenger who delivered Jackson’s demand: “Give my regards to General Jackson and tell him to bombard and be damned!” Jackson shelled the town for two days, and then turned his army around and headed for Romney, Virginia.

In late February 1862, Union Major General Nathaniel Banks’ division crossed the river at Harpers Ferry to provide protection to B&O Railroad work crews who were making repairs to the road in northwestern Virginia. A month later the work was complete and traffic resumed on the railroad for the first time in nine months.

Jackson’s victories in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign in the spring of 1862, along with General Robert E. Lee’s success on the York-James Peninsula around Richmond, showed that Union victory was far  from assured. General Lee decided to move his army out of war-torn Virginia, and on September 4, 1862, he led more than 40,000 Confederate troops across the Potomac at White’s Ford to Frederick. At one point army mules stopped in the middle of the river and refused to budge. Stonewall Jackson called on his quartermaster, John A. Harman, to clear the ford: “Harman dashed in among the wagoners, and . . . poured out a volume of oaths that would excite the admiration of the most scientific mule-driver. The effect was electrical. The drivers were frightened and swore as best they could, but far below the major’s standards. The mules caught the inspiration from a chorus of familiar words, and all at once made a break for the Maryland shore, and in five minutes the ford was cleared.”

from assured. General Lee decided to move his army out of war-torn Virginia, and on September 4, 1862, he led more than 40,000 Confederate troops across the Potomac at White’s Ford to Frederick. At one point army mules stopped in the middle of the river and refused to budge. Stonewall Jackson called on his quartermaster, John A. Harman, to clear the ford: “Harman dashed in among the wagoners, and . . . poured out a volume of oaths that would excite the admiration of the most scientific mule-driver. The effect was electrical. The drivers were frightened and swore as best they could, but far below the major’s standards. The mules caught the inspiration from a chorus of familiar words, and all at once made a break for the Maryland shore, and in five minutes the ford was cleared.”

Two squads attempted to destroy the 516-foot long Monocacy Aqueduct in order to shut down the C&O Canal for the duration of the war. “Owing to the insufficiency of our tools and the extraordinary solidity and massiveness of the masonry,” wrote an officer, both efforts failed, although soldiers did cut the canal and damaged the locks. Confederate troops also destroyed B&O Railroad bridges over the Potomac and Monocacy rivers as well as other railroad property in the region.

Lee’s plan was to move into Pennsylvania and engage Union forces there. He believed a decisive Confederate victory on Union soil could potentially end the war. His line of supply and communication with Virginia was threatened by the 12,500-man Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, however, and so he divided his army to neutralize this threat. Lee went to Hagerstown with part of Major General James Longstreet’s command, and sent three columns under the direction of Jackson to encircle Harpers Ferry. A third force guarded the South Mountain passes near Boonsboro, Maryland.

To the west, Confederate cavalry under Brigadier General John Imboden threatened Union forces guarding the railroad in northwestern Virginia. To the east, on September 11 two regiments of Confederate cavalry under Colonel Thomas Rosser occupied Westminster, Maryland.

On September 2, Union General McClellan was placed back in command of the Army of the Potomac. On September 12, his 86,000-man army marched into Frederick as the last Confederate soldiers departed. McClellan would write his wife: “I can’t describe to you for want of time the enthusiastic reception we met with . . . at Frederick. I was nearly overwhelmed and pulled to pieces. . . . In truth I was seldom more affected than by the scenes I saw . . . and the reception I met with.”

Over the next five days a chain of events drew all of these men together for what would be the bloodiest one day battle in American history. On September 13, a Union soldier found a copy of Special Order 191, Lee’s operational plan for the Confederate invasion. With the discovery of the “Lost Order,” McClellan gave chase, forcing Lee to fight a holding action in the South Mountain passes on September 14.

At the Battle of South Mountain, the Union Army of the Potomac fought for possession of three mountain gaps. The outnumbered Confederate troops who held the passes protected Lee’s widely  dispersed army. By late afternoon, the Union Six Corps took possession of Crampton’s Gap near Burkittsville, the southern-most pass, but Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin failed to aggressively follow-up his victory, which denied the Union army its only opportunity of relieving its encircled garrison at Harpers Ferry. The Union army gained possession of Fox’s Gap a little later in the evening and Turner’s Gap later in the day. That evening Lee withdrew his Confederates from South Mountain toward Sharspburg where he hoped to consolidate his army to meet the threat.

dispersed army. By late afternoon, the Union Six Corps took possession of Crampton’s Gap near Burkittsville, the southern-most pass, but Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin failed to aggressively follow-up his victory, which denied the Union army its only opportunity of relieving its encircled garrison at Harpers Ferry. The Union army gained possession of Fox’s Gap a little later in the evening and Turner’s Gap later in the day. That evening Lee withdrew his Confederates from South Mountain toward Sharspburg where he hoped to consolidate his army to meet the threat.

With disaster looming, Lee considered returning to Virginia. On September 15, however, he received word that Jackson had captured Harpers Ferry, including the nearly 12,500 Union soldiers stationed there. The surrender of Harpers Ferry caused Lee to reevaluate his plans; he decided to make a stand at the quiet farming community of Sharpsburg, Maryland.

On September 15, Lee moved his thin gray line into position along a ridge one mile west of Antietam Creek, with the Potomac River at his back. He put Longstreet in command of the center and right of the line, and Jackson in command of the left. On September 15 and 16, General McClellan deployed his forces east of the Antietam Creek. His plan was to attack Lee’s left, and when “matters looked favorably,” attack the Confederate right. If either were successful, he then hoped to strike Lee’s center.

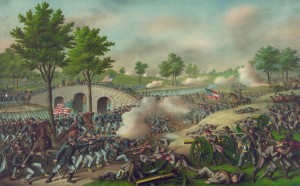

The twelve hour battle began at dawn on Wednesday, September 17, 1862. That morning three Union advances struck the Confederate left. However, McClellan’s battle plan soon broke down into a series of uncoordinated attacks. In the morning, savage combat raged across the Cornfield, East Woods, and West Woods. During this “Morning Phase,” more than 10,000 men fell killed or wounded within an area not exceeding one square mile. The carnage in the Cornfield was particularly bloody. Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker described the scene there: “In the time I am writing every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battle-field.”

By late morning, the fighting shifted toward the Confederate center at the Sunken Road. There both sides clashed for more than three hours in an indecisive stalemate that left the road and the area around it strewn with Union and Confederate dead and wounded. With the aid of a telescope, Brig. Gen. David H. Strother of McClellan’s staff observed the Confederate casualties at the lane: “Among the prostrate mass I could easily distinguish the movements of those endeavoring to crawl away from the ground; hands waving as if calling for assistance, and others struggling as if in the agonies of death.” This crude farm lane would be known as the “Bloody Lane.”

The Battle of Antietam continued as the Union Ninth Corps, commanded by Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, attempted to take the bridge on the Confederate right flank that now bears his name. Men from his command made several successive attempts to cross the bridge, but were driven back each time by Confederate artillery and riflemen positioned on a hill that overlooked the site. Finally at about 1:00 p.m. Burnside successfully carried the bridge. He then halted his advance for two hours to replenish ammunition and feed his men—a fateful delay. When Burnside renewed the advance, the Union soldiers were met by Confederate General A.P. Hill’s reinforcements, which had arrived late in the afternoon from Harpers Ferry. Confederate General Lee later wrote of Hill’s counterattack: “The progress of the enemy was immediately arrested and his lines began to waver. . . . The enemy made a brief resistance, then broke and retreated in confusion toward the Antietam.” By 6:00 pm, the battle was over. It had been the bloodiest one day battle in U.S. history. After twelve hours of fighting, there were more than 23,000 Union and Confederate casualties.

Lee withdrew his army across the Potomac on the night of September 18, virtually unopposed by McClellan. On September 20, at the Battle of Shepherdstown, the Confederates successfully drove a small pursuing Union force back across the Potomac. The evening before Confederate cavalry re-crossed the river and occupied Williamsport, which denied the Union army use of the river ford and aided the escape of Lee’s army. The following day the Confederates skirmished with Union troops and Pennsylvania militia before withdrawing back across the river.

The Battle of Antietam was nominally a Union tactical victory. It held greater significance strategically, however. The repulse of Lee’s advance into the North gave President Lincoln the opportunity to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. The Civil War now had two goals, preserving the Union and ending slavery. Defending the freedom of all Americans too had the effect of deterring England and France from supporting the Confederacy.

Following the Battle of Antietam, a number of hospitals were established in the region to treat sick and wounded soldiers. In Washington County the Union army established at least 115 temporary field hospitals in homes, barns, public buildings, and in fields. Two weeks after the battle, President Lincoln came to the region to tour the battlefield, visit the camps, and encourage General McClellan to pursue the Confederates. On October 3 Lincoln walked through a hospital that housed a number of Confederate wounded. A correspondent with the party wrote: “The President . . . remarked to the wounded Confederates that if they had no objections he would be glad to take them by the hand. . . . that many were our enemies through uncontrollable circumstances, and he bore them no malice, and could take them by the hand with sympathy and good feeling.” In the weeks that followed the battle the wounded were sent to permanent hospital facilities in Frederick, Baltimore, and other locations.

camps, and encourage General McClellan to pursue the Confederates. On October 3 Lincoln walked through a hospital that housed a number of Confederate wounded. A correspondent with the party wrote: “The President . . . remarked to the wounded Confederates that if they had no objections he would be glad to take them by the hand. . . . that many were our enemies through uncontrollable circumstances, and he bore them no malice, and could take them by the hand with sympathy and good feeling.” In the weeks that followed the battle the wounded were sent to permanent hospital facilities in Frederick, Baltimore, and other locations.

After the Battle of Antietam, General McClellan made preparations to pursue the Confederates into Virginia, using Harpers Ferry as his base of operations. The C&O Canal and the railroad bridge over the Monocacy River were repaired and engineers built pontoon bridges across the river at Berlin and Sandy Hook, Maryland. Immense quantities of supplies for the army were forwarded to these locations by railroad and canal.

Later in the year small actions occurred up and down the Potomac, including a series of cross border raids in November in the Dam Number 4 region of Washington County. The Confederates conducted raids on Poolesville on November 25 and December 14.

Gettysburg: The Highwater Mark of the Confederacy

In 1863 small unit actions continued at numerous places along the Potomac River. Confederate raider John Singleton Mosby led his “Partisan Rangers” across the Potomac near Seneca Creek on June 10 and destroyed a Union camp. By late June, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was moving into Pennsylvania for what would become the largest military campaign of the war in this region.

Lee sent Maj. Gen. Jeb Stuart’s 3,000 cavalry around the Union army to the east. The cavalry crossed the Potomac near Seneca Creek and disabled the canal. They then proceeded north, captured a Union wagon train near Rockville, and cut the B&O Railroad near Sykesville before moving on toward Westminster, Maryland.

Lee sent Brigadier General Imboden’s cavalry brigade to protect the invasion from the west. From June 17 until June 22, Imboden burned railroad bridges and damaged the canal between Cumberland and Hancock. Meanwhile, Lee’s main army crossed the Potomac River at Shepherdstown and Williamsport, where it damaged the canal. As it moved north, it destroyed railroads and detached cavalry to take livestock and supplies from the civilian population.

General Stuart led his cavalry through central Maryland, meeting his first resistance at Westminster on the afternoon of June 29. The day before, ninety-five men from the First Delaware Cavalry arrived to guard the railhead of the Western Maryland Railroad. While most of Stuart’s weary cavalry rested south of Westminster, a small party rode into town to reconnoiter. As the Virginians headed up Main Street, they were astonished to see sixty Union cavalry, led by Captain Charles Corbit, charging them with pistols and sabers. Corbit\t’s commanding officer later wrote: “Captain Corbitt[[sic], commanding Company C, was ordered to charge the column on the Washington road, which he did in a gallant and masterly manner, driving the enemy with very considerable loss until his reserve arrived, and re-enforcing the shattered column which Captain Corbit had so gallantly charged, turned again in overwhelming numbers upon Corbit and his bold followers.” The Union column was surrounded, and Corbit was taken prisoner. In the days that followed, Stuart led his cavalry into nearby Pennsylvania.

The Union army, meanwhile, raced north to meet the Confederate invasion, crossing the Potomac on pontoon bridges built across the river at Edwards Ferry, and moved through Frederick County and into Pennsylvania. On June 28 in Frederick, Maryland, Major General George G. Meade replaced Hooker in command of the Army of the Potomac, just in time to meet the Confederates at Gettysburg.

On the morning of July 1, 1863, Confederate General A.P. Hill sent the division of General Henry Heth from Cashtown on a reconnaissance in force toward Gettysburg. Soon Heth’s infantry was in sharp combat with John Buford’s Union cavalry. As the fighting intensified that morning, more troops from both sides were drawn into the escalating conflict. Union First Corps commander General John F. Reynolds was killed leading reinforcements onto the field and by the end of the day the blue coats had been forced back through the town onto the high ground of Cemetery Hill and Culps Hill.

The battle continued on July 2, as the rest of both armies arrived on the field. This day rivaled Antietam as the bloodiest in the war as more than 20,000 casualties were incurred on landmarks that would become household words in the American lexicon of military valor – the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, and Little Round Top.

The battle climaxed on July 3, in one of the bloodiest attacks in U.S. history. More than 12,000 Confederate Generals Longstreet and Hill sent more than 12,000 Confederates to participate in the doomed “Pickett’s Charge.” More than half of these men never returned from this failed attempt at breaking the center of Meade’s line. Afterwards, General Lee remarked to an observer from the British Coldstream Guards: “This has been a sad day for us, Colonel, a sad day.” In the years that followed the battle, Gettysburg went down in legend as the “High Tide” of the Confederacy.

Confederate Generals Longstreet and Hill sent more than 12,000 Confederates to participate in the doomed “Pickett’s Charge.” More than half of these men never returned from this failed attempt at breaking the center of Meade’s line. Afterwards, General Lee remarked to an observer from the British Coldstream Guards: “This has been a sad day for us, Colonel, a sad day.” In the years that followed the battle, Gettysburg went down in legend as the “High Tide” of the Confederacy.

Following the battle, the opposing sides skirmished for ten days as Lee’s army and its wagon train of wounded made its way back to the Potomac River. Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden, who was in charge of the wagon train, later wrote that “from almost every wagon for many miles issued heart-rending wails of agony. . . . From nearly every wagon . . . came cries and shrieks as these: ‘O God! Why can’t I die?’ ‘My God! Will no one have mercy and kill me?’” There was action at Monterey Pass, Smithsburg, Cunningham’s Crossroads, Hagerstown, Beaver Creek Bridge, Leitersburg, Funkstown, and Williamsport. On July 8, the Union pursuit was slowed when Stuart’s cavalry clashed with Buford and Kilpatrick’s Union cavalry at Boonsboro in the largest cavalry action in Maryland during the Civil War, involving more than 3,000 Confederate and over 5,000 Union cavalrymen.

On July 14, after a sharp fight along Falling Waters Road in Maryland, Lee got his army back to Virginia across a makeshift pontoon bridge. One of the last Confederate soldiers to cross the bridge would write: “The pontoons were being cut loose as I crossed, so I was about the last one to get over. The Yankees followed us very closely, pushing us to the very banks of the river. . . . We were shot to pieces, worn out, and very hungry.”

During the fighting at Gettysburg, Union forces were supplied from a temporary depot established at Westminster, utilizing the Western Maryland Railroad. The depot was shifted south to Frederick as Union troops pursued Lee’s retreat, and then to the Potomac at Berlin and Sandy Hook where engineers had constructed pontoon bridges over the river for Meade’s army to cross.

Small scale military operations continued to take place in the region following the Gettysburg campaign. Union cavalry fought Confederate guerillas at places such as Waterford, Virginia; Rockville, Maryland; and Charles Town, West Virginia.

The Race to Washington

By 1864, the immediate threat of a major Confederate invasion into Maryland seemed remote. Union General Grant had Lee’s army pinned down around Richmond and Petersburg. The threat reemerged, however, when Lee detached Major General Jubal Early’s Second Corps to support the Confederate defense of the Shenandoah Valley. On June 18, Early defeated a Union force under Major General David Hunter at Lynchburg, which left the Confederate commander free to march his army of about 20,000 men toward the Potomac.

To help screen Early’s advance, Mosby’s men conducted a series of raids across the Potomac, beginning with one on July 4 at Point of Rocks called the “Great Calico Raid,” so named because of the bolts of calico cloth that the raiders carried off. One newspaper reported that Mosby’s men “robbed the loyal storekeepers as well as the Rebel sympathizers, leaving nothing but crockery ware and such articles as were not easily carried off.” Mosby followed with another raid near the mouth of the Monocacy River and one near Seneca Creek.

By July 3, Early had driven Union forces out of Martinsburg, West Virginia, and the next day the Federals evacuated Harpers Ferry. Early sent cavalry under Brigadier General John McCausland to Hagerstown, where on July 6 he demanded a ransom, threatening to torch the town if it was not paid. While town officials raised the money, some of McCausland’s men looted local stores. Meanwhile Confederate cavalry units roamed the region, conducting raids on Williamsport, Sharpsburg, Boonsboro, and Middletown.

As Early prepared to leave the area, he directed parts of his command to damage the B&O Railroad and the C&O Canal between Harpers Ferry and Shepherdstown. The Frederick Examiner wrote: “The Rebel raiders and thieves seem to have made the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal the special object of their fury and wantonness in their late plundering excursion.” The Confederates badly damaged the Antietam Aqueduct and burned about eighty canal boats. By July 7, Early’s army began marching east toward Frederick, from which point he planned to continue east and capture Washington.

On July 8, General Early levied a tribute of $200,000 on the city of Frederick. The mayor raised the money from the towns’ banks. The next day Early’s advance was delayed at the Monocacy River below Frederick by a 6,000-man Union force under Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace. Wallace knew he had very little chance of defeating Early’s veterans, but hoped to delay the Confederates to buy time for reinforcements to arrive in Washington and save the capital.

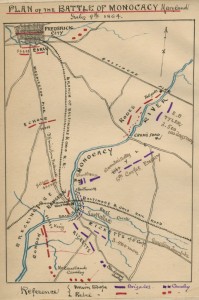

The Battle of Monocacy was fought in three major sections. Throughout the day the Confederates probed the Union right flank at the Jug Bridge across the Monocacy River. A major attack down the Georgetown Pike against the railroad junction forced the Federals to burn a covered road bridge and retreat across the river. Later, elements of Early’s right flank forded the river downstream and attacked the Union left. By late afternoon, Wallace’s line was faltering and soon the Federals were moving back toward Baltimore on the National Road. This was the only Confederate victory in a major battle on Maryland soil. While Early was free to march on Washington, the delay at Monocacy bought the Union time to reinforce the nation’s capital. From July 11–13 Early probed the defenses of Fort Stevens (near present-day Silver Spring, Maryland). Discouraged by the arrival of fresh Union troops, he abandoned the invasion and returned to Virginia. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant later wrote of Wallace’s delaying tactics at Monocacy: “General Wallace contributed on this occasion, by the defeat of the troops under him a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.”

the Union left. By late afternoon, Wallace’s line was faltering and soon the Federals were moving back toward Baltimore on the National Road. This was the only Confederate victory in a major battle on Maryland soil. While Early was free to march on Washington, the delay at Monocacy bought the Union time to reinforce the nation’s capital. From July 11–13 Early probed the defenses of Fort Stevens (near present-day Silver Spring, Maryland). Discouraged by the arrival of fresh Union troops, he abandoned the invasion and returned to Virginia. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant later wrote of Wallace’s delaying tactics at Monocacy: “General Wallace contributed on this occasion, by the defeat of the troops under him a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.”

On July 29 Early sent part of his army back into Maryland to screen the movement of McCausland’s cavalry toward Chambersburg. A force was dispatched to Martinsburg to destroy the B&O Railroad, while Confederate cavalry moved toward the Potomac and crossed the river. The Confederates drove Federal troops out of Williamsport and its cavalry occupied Hagerstown. There they fought in the streets with Union cavalry, driving the Union troops back to Greencastle. Afterward, the Confederate soldiers stayed in Hagerstown, broke into shops, looted and burned warehouses, and destroyed a train filled with supplies before returning to Virginia. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant later wrote of Wallace’s delaying tactics at Monocacy: “General Wallace contributed on this occasion, by the defeat of the troops under him a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.”

When Chambersburg’s citizens failed to come up with a ransom on July 30, 1864, McCausland burned the town. Early later explained that local citizens said “that they were not afraid of having their town burned, and that a Federal force was approaching. The policy pursued by our army on former occasions had been so lenient that they did not suppose the threat was in earnest this time . . . .McCausland, however, proceeded to carry out his orders, and the greater part of the town was laid in ashes.” McCausland then led his command west toward Hancock. In an attempt to keep pressure off of McCausland’s column, Early once again sent diversionary forces into Maryland. On August 4 Confederates crossed the river near Shepherdstown and Harpers Ferry. The following day Confederate infantry and cavalry occupied Williamsport, Hagerstown, Keedysville, and Sharpsburg.

The last Civil War combat on Maryland soil took place early on the morning of August 5, 1864. The First Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry battalion drove Confederate cavalry out of Keedysville. The cumulative effect of these Confederate movements along the Potomac had been to create the impression of a broad Confederate front poised to invade the North. Northern newspapers speculated that another invasion was taking place.

Early’s movements in the summer of 1864 were the last major Confederate incursions into the region during the Civil War. In August, Major General Philip H. Sheridan was charged with ridding the Shenandoah Valley of the Confederates. He defeated Early in three major battles in the Shenandoah Valley in a thirty-day period, which had the effect of suppressing raids into Maryland and allowing for both the railroad and the canal to be repaired and resume operations. After the second Union victory, General-in-Chief Grant wrote: “It [the Battle of Fishers Hill] will open again to the Government and to the public the very important line of road from Baltimore to the Ohio, and also the Chesapeake Canal.”

One notorious small-scale operation occurred in the region on October 13 when Mosby’s Rangers derailed a train west of Harpers Ferry and discovered two Federal paymasters on board. The rangers carried off over $100,000 in U.S. currency in what they later called the “Greenback Raid.”

War Draws to a Close

No major operations took place in the region in 1865. Incursions across the Potomac by small bands of Confederate raiders took place early in the year at Edwards Ferry and near the Monocacy River. On January 19 Mosby’s men derailed yet another train near Harpers Ferry in what became known as the “Coffee Raid,” as the train was carrying delicacies for Union officers.

During skirmishes preceding the Battle of Monocacy in 1864, Union General Lew Wallace was astonished to see citizens of Frederick, Maryland, watching the fighting with seemingly no heed to the dangers involved. After the war, Wallace wrote that “Frederick City and the region around it had been a playground for the game of war from its first year, and the people had grown so used to it in all its forms that even battle had ceased to have terrors for them.” Wallace overstated the point a bit, but the region from Gettysburg and Chambersburg down through mid-Maryland and across the Potomac into northern Virginia had certainly witnessed its share of war by the close of the conflict. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers had tramped through the territory, and thousands were buried as casualties of the fighting. Many sons, fathers, and husbands from the region likewise would not return to their loved ones. The damage to homes, farms, churches, stores, and other buildings was almost incalculable, as certainly was the more insidious damage to families and communities split by the war. The war was over, the Union had been preserved, and slavery had been abolished, but the effects of the war would last for a very long time indeed.

The following people contributed to this essay: Ted Alexander, National Park Service, Chief Historian at Antietam National Battlefield and author of The Battle of Antietam: The Bloodiest Day (2011), and Timothy Snyder, M.A., author of Trembling in the Balance: The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal During the Civil War (2011).