See The Sites

All Sites

- Battlefields / Military

- Homefront

- Historic Buildings

- African American

- Museums / Archives

- Cemeteries / Monuments

- National / State Parks

Angela Kirkham Davis House

29 West Baltimore Street Funkstown, MD 21734Former home of Angela Kirkham Davis who chronicled her experiences as a Union sympathizer. The house also served as a hospital after the Battles of Antietam and Funkstown. Angela Kirkham Davis was a Union supporter who cared for wounded soldiers of both sides during the Battle of Antietam in September 1862 and again in 1863 after the Battle of Funkstown. With her husband Joseph Davis, she brought food and water to the battlefield and took a wounded officer into her home to recuperate. Davis recounted her wartime experiences in War Reminiscences: A Letter to my Nieces. This home is a private residence.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-I-554 in search box to right of “Site No.”) Roger Keller, Crossroads of War – Washington County, Maryland in the Civil War (Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 1997), 3-33.

Historical Marker Database: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=2008

Antietam National Battlefield

5831 Dunker Church Road Sharpsburg, MD 21782 http://www.nps.gov/anti/ (301) 432-5124A pivotal battle of the Civil War, the Battle of Antietam was fought on September 17, 1862, and was the bloodiest single day of combat ever on American soil. After the General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate incursion into Maryland in early September 1862, the Union Army under General George B. McClellan pursued Lee with uncharacteristic speed thanks to the finding of the famous “Lost Orders 191” that detailed Lee’s movements. Lee had divided his army to accomplish various objectives, but once McClellan began pursuit, Lee quickly tried to reconsolidate his forces. A delaying action at South Mountain on September 14 slowed the Union troops long enough for Lee to establish a defensive line at Sharpsburg, MD. The resulting battle on September 17 was a pivotal battle of the war. Although McClellan’s troops outnumbered the Confederates, the day long battle was virtually a stalemate. The intense fighting was brutal, however, and the Battle of Antietam became the single bloodiest day of fighting, in terms of casualties, during the war. The only skirmishes on the 18th came as Lee withdrew his troops across the nearby Potomac River back to Virginia. While it was no clear victory for either side, Union soldiers did manage to halt the Southern advance into the north, and Lee’s expulsion from Maryland was touted as a victory. Lincoln used it as a chance to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 23rd, which changed the objective of the war from restoring the Union to also include the elimination of slavery. The Confederates’ inability to win a decisive victory on Northern soil and the altered objectives of the war also influenced England and France to not recognize the Confederate States of America as a sovereign nation, a critical development that helped the North win the war. The battlefield was established as a national park in 1890, and was administered by the War Department until 1933, when it was turned over to the National Park Service. The park includes many historic structures and monuments, and the Visitor Center includes exhibits, a theater and a bookstore.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Antietam National Battlefield website: http://www.nps.gov/anti/ http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/hh/31/index.htm (National Park Service’s Antietam Historical Handbook)

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://www.marylandhistoricaltrust.net/NR/NRDBDetail.aspx?HDID=12

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1073

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0477 in search box to right of “Site No.”) Civil War Sites Advisory Commission’s Battle Summary for Antietam:

http://www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/md003.htm

Civil War Trust: http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/antietam.html

Susan Cooke Soderberg, A Guide to Civil War Sites in Maryland – Blue and Gray in a Border State (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, 1998): 107-111

Save Historic Antietam Foundation: http://shaf.org/

Antietam National Cemetery

Shepherdstown Pike (MD 34) Sharpsburg, MD 21782The cemetery holds the remains of over 4,700 Union soldiers killed at Antietam and other nearby battlefields. Legislation to establish a cemetery at Antietam was introduced in 1864 by Maryland State Senator Lewis P. Firey. Though it was originally intended to receive both Union and Confederate dead, anti-Southern feeling among the Northern states prompted a Union-only policy. (Southern dead were sent to other cemeteries in the area, including Elmwood Cemetery in Shepherdstown, Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown, and Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick.) Prominent local doctor Augustin A. Biggs was chosen as the designer and first superintendent of the cemetery, and work began in 1866, with former Union soldiers as most of the laborers. Six thousand coffins were provided by the U.S. government for the dead, who were interred by state (when known). The dedication ceremony took place on September 17th, 1867, and was attended by President Andrew Johnson, who gave a speech for the occasion. Altogether, the cemetery holds 4,776 Union remains from Antietam, South Mountain, Monocacy, and other Maryland battles. Over two hundred other soldiers from later wars (Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, Korean War) are buried there as well. The cemetery was closed to future burials in 1953, though an exception was made in 2000 for a Keedysville soldier killed in the USS Cole explosion.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://home.nps.gov/anti/historyculture/antietam-national-cemetery.htm

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1078; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1079;http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1080

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0356 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Washington County, Maryland – A Guide to 66 points of Interest(Shepherdstown, WV: Charles S. Adams, 1996), 9-10.

Arcadia

47200 Buckeystown Pike Adamstown, MD 21710Arcadia was occupied by soldiers from both sides during the war, and served as a hospital for Confederate soldiers after the Battle of Monocacy. Arcadia, built c.1780, was owned by Robert McGill in 1862. In 1863, just prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, Arcadia served as the headquarters of Union General George Meade, then the newly appointed commander of the Army of the Potomac. After the Battle of Monocacy in 1864 wounded Confederate soldiers were taken to the house for treatment. Dr. David McKinney, the surgeon in charge of the Federal hospital across Ballenger Creek, was so impressed by Arcadia that he purchased it from Robert McGill in 1865. Arcadia is now a private residence.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (enter F-1-172 in “Site No.” in “Search by Property” tab)

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=485&COUNTY=Frederick&FROM=NRCountyList.aspx?COUNTY=Frederick

Barbara Fritchie House

154 West Patrick Street Frederick, MD 21701 Contact: The house is privately owned and occasionally opened for tours. Check with the Tourism Council of Frederick County for current information: 301-600-2888, or 800-999-3613This reconstructed house marks the residence of Barbara Fritchie, the heroine of John Greenleaf Whittier’s 1863 poem. In 1863, John Greenleaf Whittier wrote a poem about Frederick resident Barbara Fritchie and her courageous act of flying the Union flag from her attic window above of the heads of Confederate soldiers marching out of town during the first invasion of Lee’s troops into Maryland in September 1862. Fritchie was ninety-six years old at the time, and perhaps bedridden. The poem has been controversial ever since, and most people today think the incident never took place (at least not the version described in the poem). Barbara Fritchie’s strong Unionist views were never in doubt, however. She freely expressed her strong and unyielding support for the Union throughout the sectional conflict. It is known that Barbara Fritchie stood outside her home and cheered on McClellan’s forces as they marched through Frederick in September 1862, and an alleged member of Jackson’s Third Brigade relates that the elderly woman once mistakenly waved a Union flag at passing Confederates. True or not, Whittier’s poem became famous, and spawned books, plays, musicals, films, and memorabilia and souvenirs of all types. Fritchie died in December of 1862, and her house was torn down a few years later to widen nearby Carroll Creek. Much of the material from the house was saved, and later used in reconstructing the house in the 1920s. The house is privately owned and occasionally open for tours.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter FHD-0520 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Frederick County, Maryland – A Guide to 49 Historic Points of Interest (Shepherdstown, WV: The Author, 1995), 12

Civil War Trails Historical Marker: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=2693

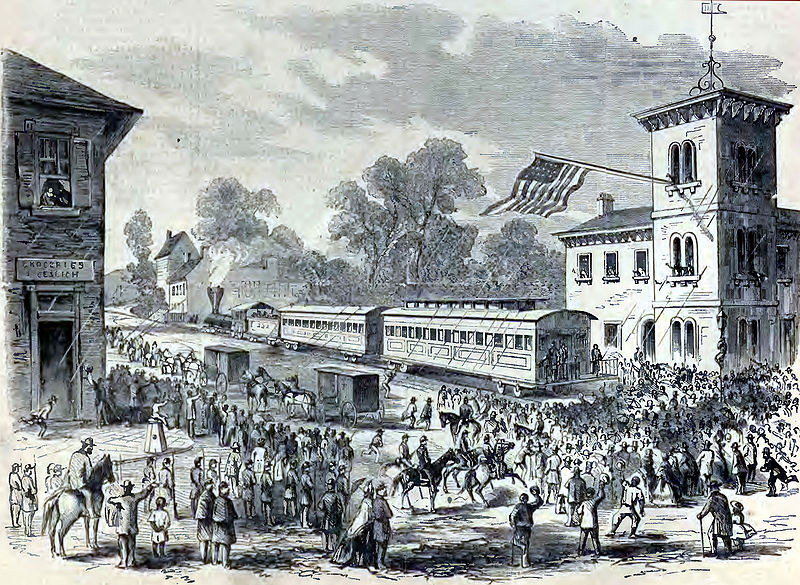

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Station

100 South Market Street Frederick, MD 21701

After visiting the Antietam battlefield and a wounded Union general in Frederick, President Abraham Lincoln gave a brief speech here on October 4th, 1862, before boarding a train to Washington. The Frederick passenger station of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was constructed in 1854, replacing an older station. During the Civil War, the station was a vital transportation hub for troops and supplies. The station witnessed several notable events. In 1859, a militia company from Frederick boarded a train here for Harpers Ferry to join the fight against John Brown and his raiders. Two years later, in September 1861, several pro-secession members of the Maryland Legislature, then meeting in Frederick, were arrested and placed on trains here to be taken to Baltimore. Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney’s funeral car arrived here on October 15th, 1864. But perhaps the most illustrious event at the train station occurred in 1862. President Abraham Lincoln arrived in Frederick on October 4, 1862, after visiting the Army of the Potomac at Sharpsburg following the Battle of Antietam. Lincoln arrived in an ambulance wagon, and visited Union General George Hartsuff at the Ramsey house on Record Street, where Hartsuff was recovering from a wound received at Antietam. As Lincoln and his party made their way to the train station for the return trip to Washington, “a vast concourse of people” assembled to see the President. Before the train departed, Lincoln appeared on the rear platform of his car and gave a brief speech:

After visiting the Antietam battlefield and a wounded Union general in Frederick, President Abraham Lincoln gave a brief speech here on October 4th, 1862, before boarding a train to Washington. The Frederick passenger station of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was constructed in 1854, replacing an older station. During the Civil War, the station was a vital transportation hub for troops and supplies. The station witnessed several notable events. In 1859, a militia company from Frederick boarded a train here for Harpers Ferry to join the fight against John Brown and his raiders. Two years later, in September 1861, several pro-secession members of the Maryland Legislature, then meeting in Frederick, were arrested and placed on trains here to be taken to Baltimore. Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney’s funeral car arrived here on October 15th, 1864. But perhaps the most illustrious event at the train station occurred in 1862. President Abraham Lincoln arrived in Frederick on October 4, 1862, after visiting the Army of the Potomac at Sharpsburg following the Battle of Antietam. Lincoln arrived in an ambulance wagon, and visited Union General George Hartsuff at the Ramsey house on Record Street, where Hartsuff was recovering from a wound received at Antietam. As Lincoln and his party made their way to the train station for the return trip to Washington, “a vast concourse of people” assembled to see the President. Before the train departed, Lincoln appeared on the rear platform of his car and gave a brief speech:

“FELLOW-CITIZENS,—I see myself surrounded by soldiers and by the citizens of this good city of Frederick, all anxious to hear something from me. Nevertheless, I can only say—as I did elsewhere five minutes ago—that it is not proper for me to make speeches in my present position. I return thanks to our gallant soldiers for the good service they have rendered, the energies they have shown, the hardships they have endured, and the blood they have so nobly shed for this dear Union of ours. And I also return thanks, not only, to the soldiers, but to the good citizens of Frederick, and to all the good men, women, and children throughout this land for their devotion to our glorious cause. And I say this without any malice in my heart toward those who have done otherwise. May our children, and our children’s children, for a thousand generations, continue to enjoy the benefits conferred upon us by a united country, and have cause yet to rejoice under those glorious institutions bequeathed us by Washington and his compeers! Now, my friends—soldiers and citizens—I can only say once more—Farewell!”

The station is now home to the Frederick Community Action Agency.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/MD0679/

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter FHD-0030 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

David S. Lovelace, “John Brown’s Raid, Edward Shriver, and the Frederick Militia,” Catoctin History (Issue# 11, 2009): 34-37.

“Maryland Legislature,” The Valley Register (Middletown, MD), September 20, 1861, 2.

“The President’s Visit to McClellan’s Army,” Harper’s Weekly, October 25, 1862, 684, 686.

“President Lincoln Stopped Off Here On Way Back From Antietam Battlefield,” Frederick News, September 1, 1961, 19.

Battle of Monterey Pass

Blue Ridge Summit, PA17214 http://www.montereypassbattlefield.org/In the July 4, 1863 Battle of Monterey Pass, Confederate cavalry attempted to hold off Union cavalry that sought to attack the Southern wagon train retreating from Gettysburg. On the morning ofJuly 4, 1863the Union cavalry division commanded by Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick was ordered to attack a Confederate wagon train retreating fromGettysburgon the road running betweenFairfieldandWaynesboro,Pennsylvania. Informed by local citizens that the Confederates were crossing atMontereyPass, a gap inSouthMountain, Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s cavalry brigade reached the base of the gap at about sundown. In rain and darkness, Custer’sMichiganhorsemen attacked the Confederates defending the pass. In the chaotic fighting that followed, other Union troops advanced up the mountain, threatening to outflank the Confederates, who withdrew further up the summit. A charge by the First West Virginia Cavalry gained the mountain summit and resulted in the capture of a Confederate artillery piece. In wild confusion, a number of wagon teams bolted down the western slope of the pass and crashed into ravines or ran off of cliffs. Union cavalry took over 1,500 prisoners and captured dozens of wagons, many of which were subsequently burned, as the fight spilled over the Mason-Dixon Line. About 10,000 soldiers were involved in the Battle of Monterey Pass, which makes it the second largest battle fought onPennsylvaniasoil, following only the Battle of Gettysburg.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.montereypassbattlefield.org/

http://www.montereypassbattlefield.org/contents/history_of_the_battle.htm

Eric J. Wittenberg, J. David Petruzzi and Michael F. Nugent, One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4–14, 1863, 2008.

Kent Masterson Brown, Retreat from Gettysburg: Lee, Logistics, and the Pennsylvania Campaign, 2005.

Civil War Trails marker: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=30968

http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=31046

Other markers: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=31047

http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=30981

http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=31034

Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park

Park Headquarters 1850 Dual Highway, Suite 100 Hagerstown, MD 21740 http://www.nps.gov/CHOH (301) 739-4200The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal was an important supply line for the Union, and was often a target of Confederate troops. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was built between 1828 and 1850, running 184.5 miles from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland; it operated until 1924. During the war, it was an important supply line for the Union, and was sabotaged by the Confederates several times, most notably as they were retreating from Harpers Ferry in 1862. The Confederates were able to successfully occupy Harpers Ferry on September 15, 1862, partly because of the lack of Union fortifications at nearby Fort Duncan. After the town and garrison were re-occupied by the Union army in October 1862, Maryland Heights, overlooking the canal and Harpers Ferry, and Loudoun Heights, across the Potomac River in Virginia, were heavily fortified.

See these sources and websites for additional information: http://www.nps.gov/CHOH National Register of Historic Places summary: http://mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=14&COUNTY=Frederick&FROM=NRCountyList.aspx?COUNTY=Frederick

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: many reports on various Chesapeake and Ohio Canal structures; go to http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/habs_haer/index.html and enter “Chesapeake and Ohio Canal” in search box.

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter F-2-011 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Doubleday Hill

S. Commerce andW. SalisburyStreets WilliamsportMD21795 (301)223-7711 http://www.williamsportmd.gov/doubleday_hill.htmlDoubleday Hill was the site of an early Union battery that was established atWilliamsport,Marylandon a hill that overlooked a prominent ford on thePotomac River. Capt. Abner Doubleday, aWest Pointgraduate, commanded a battery atFortSumterand fired the first Union reply to the Confederate bombardment. Assigned to Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson’s Department of Pennsylvania, onJune 18, 1861Doubleday brought a three-gun “heavy battery” toWilliamsport, consisting of artillery pieces that fired twenty- and thirty-pound projectiles. He established his battery on a hill that overlooked a prominent ford over thePotomac River, which became known as “Battery Hill” or “Doubleday Hill.” The battery helped protect Patterson’s army when it crossed the river on July 2 and engaged Confederate forces in the Battle of Falling Waters. Owned by the town ofWilliamsport, in 1897 three iron cannon were placed on the hill, and a flag pole was later installed, to commemorate the site’s importance. In 2012 the town ofWilliamsportreceived a grant to, in part, restore Doubleday Hill to its appearance in 1861.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.williamsportmd.gov/doubleday_hill.html http://www.herald-mail.com/news/local/hm-williamsport-town-council-briefs-20120813,0,5502791.story

S. Roger Keller, Events of the Civil War in Washington County, Maryland, 1995. Robert Patterson, A Narrative of the Campaign in the Valley of the Shenandoah, in 1861, 1865.

MarylandInventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-WIL-381 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Other markers: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=51872&Result=1

Dunker Church

5831 Dunker Church Road Sharpsburg, MD 21782This small church was the central point of a number of Union attacks on the Confederate left flank during the Battle of Antietam. The Dunker church was originally built in 1852, on land donated by local farmer Samuel Mumma. It was the site of General Stonewall Jackson’s stand against the Union I and XII Corps, and the focal point of several Union attacks against the Confederate left flank. Though it was nearly destroyed during the intense fighting that surrounded it on the morning of September 17th, it was used as a temporary medical aid station after the battle, and was the site of a truce called on September 18th in order to exchange wounded soldiers and bury the dead. It may have been used as an embalming station by the Union Army. Tradition also holds that it was visited by President Lincoln on his tour of the battlefield in October 1862. It was rebuilt after the devastation of the war only to be destroyed by a windstorm in 1921; many of the pews and bricks were saved, and it was reconstructed in 1961 according to the original plans and using some original materials. One of its attractions is its Mumma Bible, the pulpit bible that was carried off during the war by a member of the 107th New York Regiment and returned years later.

See these sources and websites for additional information: http://www.nps.gov/anti/historyculture/dunkerchurch.htm

Historic American Buildings Survey /Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md0588

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/(Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0352 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Washington County, Maryland – A Guide to 66 points of Interest(Shepherdstown, WV: Charles S. Adams, 1996), 3

Historical Marker Database: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=20593

Entler Hotel (Historic Shepherdstown Museum)

129 E. German Street Shepherdstown, WV 25443 Contact: 304-876-0910 http://historicshepherdstown.comThe hotel served as a hospital complex after the Battle of Antietam. The Entler Hotel began as a set of six adjacent properties, the earliest of which was built in 1786. After the Battle of Antietam in 1862, it was turned into a large hospital; some of the most severely wounded soldiers were brought here and tended by a local doctor, Richard Parran. After the war, it resumed its status as a hotel: in the latter part of the century, it was not uncommon for a veteran of the Civil War to return to spend a night in the room in which he had recuperated. In 1912 the structure became Rumsey Hall, the first men’s dormitory of Shepherd College. After serving as faculty apartments and storage space, it lay abandoned for almost a decade and was threatened with destruction. Today, however, it is the headquarters of the nonprofit organization Historic Shepherdstown, and is operated as the Historic Shepherdstown Museum.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.historicshepherdstown.com/

National Register of Historic Places nomination: http://www.wvculture.org/shpo/nr/pdf/jefferson/73001919.pdf

Margaret S. Creighton, The Colors of Courage – Gettysburg’s Forgotten History(NY: Basic Books, 2005), 121-122.

Evangelical Reformed Church

15 West Church Street Frederick, MD 21701 Contact: 301-662-2762Confederate General Stonewall Jackson attended services here on September 7, 1862, during the Confederates’ first foray into Maryland that would end at the Battle of Antietam. In the Antietam Campaign, the Confederate Army first entered Maryland on September 4, 1862. The CSA soldiers stayed in the Frederick vicinity for several days, until September 12. General Stonewall Jackson, deeply religious, planned to attend Sunday evening church services on September 7 at Frederick’s Presbyterian Church, where the minister, Rev. Dr. John Ross, was a personal friend. But services were not held that evening at the Presbyterian Church, so Jackson and a few fellow officers attended the services of the Evangelical Reformed Church just down the street. The pastor of the Evangelical Reformed Church, Dr. Daniel Zacharias, was a strong Unionist but also had two sons fighting on the Confederate side. Dr. Zacharias was later praised for his courage in offering a prayer for President Abraham Lincoln while Confederate officers were in the congregation, but according to one of Jackson’s aides, the General, as was his custom, promptly fell asleep when the sermon started and never heard the prayer. Henry Kyd Douglas, the aide, later wrote that if Jackson had been awake to hear the prayer, “I’ve no doubt he would have joined in it heartily.” It is unclear whether General Jackson was awake when the hymn, “The Stoutest Rebel must Resign,” was sung.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter FHD-0664 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Kathleen A. Ernst, Too Afraid to Cry – Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999), 48-49.

John H. Landis, “A Lancaster Girl in History,” in Papers Read Before the Lancaster Historical Society Vol. 23, No. 5 (Lancaster, PA: The New Era Printing Co., 1919), 87.

Fort Frederick State Park

11100 Fort Frederick Road Big Pool, MD 21711 (301)842-2155 http://dnr.maryland.gov/publiclands/western/fortfrederick.aspThis French and Indian War-era stone fort was used during the Civil War as a picket outpost and was the scene of a Christmas Day skirmish in 1861. FortFrederickwas built byMaryland’s colonial government in 1756 to provide protection to frontier settlers from Indian raids. Named for the last Lord Baltimore, distinctive quadrangle bastions were constructed at each corner of the fort. During the Revolutionary War it housed British prisoners. Just prior to the Civil War, Nathan Williams, a free black man, bought and farmed the property. In order to provide protection to the nearby Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, Union pickets were stationed in and near the fort. In December 1861, during Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s three raids again Dam Number 5, the First Maryland Infantry, commanded by Col. John Kenly, was ordered to the area and established pickets between Four Locks and Cherry Run, including Company H posted atFortFrederick. OnDecember 25, 1861, this company engaged in a skirmish with Confederates on theVirginiaside of the river. The fort was also used as a picket outpost at other times during the war. After the war, Nathan Williams continued to farm the property, demolishing portions of the fort. After his death in 1884, the property passed into the hands of his family who sold it in 1911. In 1922 the state ofMarylandacquired the property. In the 1930s, the walls of the fort were rebuilt and restored with the assistance of the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Great Depression-era agency created to alleviate national unemployment. Fort Frederick became Maryland’s first state park.

See these sources and websites for additional information: http://dnr.maryland.gov/publiclands/western/fortfrederick.asp

Allan Powell, Fort Frederick: Potomac Outpost, 1988. Chas. Camper and J. W. Kirkley, Historical Record of the First Regiment Maryland Infantry, 1871.

National Historical Landmarks summary: http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=1338&ResourceType=Structure

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Photos/73000939.pdf http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/73000939.pdf

Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/item/md0835.photos.084992p/

MarylandInventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-V-205 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Civil War Trails markers: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=821 http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=5571 Other markers: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=681

Gettysburg National Military Park

1195 Baltimore Pike Gettysburg, PA 17325 Contact: (717) 334-1124 ext. 8023 http://www.nps.gov/gett The park, created in 1894, preserves and commemorates the Battle of Gettysburg, fought July 1-3, 1863.The Battle of Gettysburg, fought July 1-3, 1863, was a turning point in the Civil War. The battle is often referred to as the “high-water mark of the Confederacy,” since this was the final large-scale push into Northern territory during the war. Although more men died during the three days of the battle than in any battle fought before or since on North American soil, the Union victory did much to boost the morale of northern soldiers and civilians alike. Efforts at commemorating the Battle of Gettysburg began almost immediately, as the citizens of Gettysburg were forced to cope with the slaughter that had taken place on their farms and in their streets. Burial ceremonies led to the creation of a cemetery there, the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, which became part of the larger national cemetery system in 1872. As early as 1863, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association was established and began attempting to purchase land and preserve the battlefield. The Association’s original aim was to preserve only the Union battle lines, with very little effort at commemorating the Confederate positions until 1892. These efforts eventually led to the creation of a National Military Park in 1894; it, like the cemetery, was administered by the War Department from the time of its creation until 1933, when the National Park Service took over. An estimated 9,600 acres comprise the Battle of Gettysburg’s primary area of action. Monuments and markers are scattered across the battlefield, and the park includes a Museum and Visitors Center.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Civil War Sites Advisory Commission’s Battle Summary: http://www.nps.gov/history/hps/abpp/battles/pa002.htm

Civil War Trust: http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/gettysburg.html

Gettysburg Railroad Station

35 Carlisle Street Gettysburg, PA 17325 (800)337-5015 http://www.gettysburg.travel/visitor/member_detail.asp?contact_id=34438The Gettysburg Railroad Station served as a field hospital following the Battle of Gettysburg, and President Lincoln later passed through it to give the Gettysburg Address. Construction of the Gettysburg Railroad began in 1856 and was completed in 1858. The line extended for sixteen miles, running between Hanover Junction andGettysburg,Pennsylvania. Construction of the train station was completed in 1859. During the Battle of Gettysburg, the train station was utilized as a field hospital. After the battle, the Union army commandeered the railroad for about six weeks to remove the wounded and forward supplies. About 15,000 wounded soldiers were evacuated from the battlefield over the Gettysburg Railroad. In the days leading up to the dedication of Soldiers’NationalCemetery, about 15,000 dignitaries and guests arrived in town, most of whom traveled over the Gettysburg Railroad and passed through the train station, including President Lincoln on November 18. The next day at the dedication,Lincolndelivered “a few appropriate remarks,” which have become immortalized as the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln departed that evening, again using the Gettysburg Railroad on his party’s return to Washington. After various changes of ownership due to the sale and mergers of railroads over the decades since the Civil War, in 1998 title to the Gettysburg Railroad station was transferred to the Borough of Gettysburg, which undertook efforts to restore and preserve the building. After $1 million was raised, the building was restored and is now serving as a visitor information center for the Gettysburg Convention and Visitors Bureau.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.gettysburg.travel/visitor/member_detail.asp?contact_id=34438

http://www.hallowedground.org/Explore-the-Journey/Historical-Site/Historic-Gettysburg-Train-Station http://www.gettysburg.travel/media/news_detail.asp?news_id=408

Gerald Bennett, The Gettysburg Railroad Station, 1999; revised 2008

Harpers Ferry National Historic Park

171 Shoreline Drive Harpers Ferry, WV 25425 Contact: (304) 535-6029 http://www.nps.gov/hafeThe site of John Brown’s raid in 1859, Harpers Ferry was also strategically important during the war years, and changed hands several times. Harpers Ferry played a significant role in the Civil War, from John Brown’s raid before the war, to the U.S. Arsenal located in town, and to the numerous times the town changed hands during the course of the war. Harpers Ferry was strategically important because of the Arsenal and the town’s railroad, highway, and canal transportation links. John Brown chose Harpers Ferry as his first objective in his infamous 1859 raid because of its stores of weapons and its location near the mountains; his plan was to establish a sheltered base from which to free slaves and attack slaveholders. Brown launched his raid on October 16th, 1859. However, he did not draw the support he expected from local slaves, and he was pinned down by the local militia until U.S. Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived, capturing or killing Brown and his men. Brown was taken to nearby Charles Town, where he was tried and executed. Brown’s raid is widely credited with helping fan the flames of the impending conflict. The Civil War reached Harpers Ferry on April 18th, 1861, when Union forces burned the arsenals located there to deny access to the “strong and hostile Virginia State forces” reported to be approaching. The Confederates in their turn burned more buildings and looted others in June 1861. Harpers Ferry was regained and occupied by Federal forces from February-September 1862, but their defenses were weak. Confederates under the command of Stonewall Jackson were able to take the town in an astonishingly short amount of time as part of Lee’s Maryland campaign, on September 15th, 1862, taking 12,000 Union prisoners in the process. Union forces once again won back Harpers Ferry in October, and immediately began strengthening its defenses, building fortifications until June 1863. In 1864, the rifle trench along Bolivar Heights was extended so that the town was virtually impregnable, provided the defenders also held Loudoun Heights and Maryland Heights (site of Federal campgrounds from 1862-1865 and seven fortifications, only one of which is still intact today). From August 1864 to February 1865, Harpers Ferry was the main base of operations for Union General Philip Sheridan’s army while they destroyed Confederate General Jubal Early’s forces and took control of the Shenandoah Valley. In 1864, Federal forces destroyed several more buildings around the area, this time to clear the way for a U.S. Military railroad to help supply Sheridan’s army. After the Civil War, Harpers Ferry was the site of Storer College, one of the earliest institutions for black education after Emancipation.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://www.marylandhistoricaltrust.net/NR/NRDBDetail.aspx?HDID=18

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-III-072 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Hessian Barracks

242 South Market Street Frederick, MD 21701This former barracks and prison served throughout the war as a hospital for the North and the South. The Hessian Barracks are generally assumed to have been built in 1777, though several local historians contend that they were built earlier, during the French & Indian War. They served as a prison during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, as well as holding French prisoners captured from ships during America’s undeclared war with France at the end of the 18th century. Just prior to the Civil War, the barracks were used as a meeting place for Frederick’s Home Guard. Soon after the war began, the remaining two buildings and the grounds were designated as a Union Military Hospital. As casualties mounted from nearby battles, new buildings were added and the hospital became one of the largest military hospitals in the country. The hospital remained in operation until the end of the war. The hospital was of great importance especially during the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam, caring for wounded soldiers from both the Union and the Confederacy.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=46&COUNTY=Frederick&FROM=NRCountyList.aspx?COUNTY=Frederick

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md0336

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter FHD-0243 in search box to right of “Site No.”) Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Frederick County, Maryland – A Guide to 49 Historic Points of Interest(Shepherdstown, WV: The Author, 1995), 14

Civil War Trails Historical Marker: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=2806

Historical Marker Database: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=2739

Hitt Bridge (Upper Bridge)

Keedysville Road over Antietam Creek Keedysville, MD 21756Hitt Bridge is one of three stone arch bridges significant in the Battle of Antietam. The Hitt Bridge (sometimes called the Upper Bridge) was named for local landholder Samuel Hitt, and was completed in 1830 by Silas Harry. Its distinguishing feature is its unusually high center arch. The bridge was the main artery for Union troops on their way to engage the Confederates at Sharpsburg, and was briefly the campsite of General Joseph Mansfield’s Union XII Corps.

See these sources and websites for additional information: Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1128

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0122 in search box to right of “Site No.”) Historical Marker Database: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=3201

Jennie Wade House

548 Baltimore Street Gettysburg, PA 17325 Tour information: (717) 334-4100 http://www.jennie-wade-house.comJennie (or Ginnie) Wade was shot and killed in this house during the Battle of Gettysburg. She was the only civilian casualty of the battle. Jennie (Ginnie) Wade, a native of Gettysburg, was twenty years old when the Battle of Gettysburg began on July 1, 1863. [Her full name was Mary Virginia Wade, and she was nicknamed "Ginnie." Newspaper reports after the battle mistakenly referred to her as "Jennie."] On the first day of the battle, Ginnie, her mother, and two younger brothers left their house on Breckenridge Street to assist Ginnie’s sister, Georgia Wade McClellan, and her new baby, in the McClellan home on Baltimore Street. On the morning of July 3, while Ginnie was kneading dough for bread, a bullet fired by an unknown soldier tore through the kitchen door and struck Ginnie. She died instantly. Amazingly, Ginnie was the only civilian casualty during the three-day battle. The McClellan house, now called the Jennie Wade House, is a museum and tourist attraction.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.jennie-wade-house.com/ http://www.army.mil/gettysburg/profiles/wade.html

Margaret S. Creighton, The Colors of Courage – Gettysburg’s Forgotten History (NY: Basic Books, 2005), 121-122.

Kemp Hall

2-4 East Church Street Frederick, MD 21701 301-662-2762 [Evangelical Reformed United Church of Christ, owner]The pro-secessionist Maryland General Assembly met in Kemp Hall between April and September 1861. In late April 1861, Maryland Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks called a special session of the Maryland General Assembly to discuss the state’s position in the impending war. Annapolis was under federal occupation, so Hicks moved the session to Frederick. Hicks and the majority of the citizens of Frederick were pro-Union, but a majority of the legislators were pro-Southern. The General Assembly convened on April 26 in the Frederick County Courthouse, but finding the courthouse too small, the legislature met on the second day in Kemp Hall, a building owned by the German Reformed Church. The Senate met on the third floor and the House met on the second. During the April session, the assembly passed resolutions encouraging peaceful solutions to the problem of secession, and adjourned on May 14th. Several other meetings were held over the summer. Governor Hicks and President Abraham Lincoln were determined that Maryland remain in the Union. Several pro-secession delegates had already been arrested elsewhere in the state. As the Assembly prepared to reconvene in September 1861, and possibly vote on secession, the Secretary of War ordered the imprisonment of the remaining secessionist legislators. The Frederick meeting of the General Assembly came to an end on September 17, when the session was adjourned for lack of a quorum.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter FHD-0607 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

“The General Assembly Moves to Frederick, 1861,” on the Maryland State Archives website at http://www.msa.md.gov/msa/stagser/s1259/121/7590/html/0000.html

“Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861,” part of Teaching American History in Maryland, at http://teachingamericanhistorymd.net/000001/000000/000017/html/t17.html

“Maryland Legislature,” The Valley Register(Middletown, MD), September 20, 1861, 2.

Carl N. Everstine, The General Assembly of Maryland, 1850-1920(Charlottesville, VA: The Michie Co., 1984), 91-141.

Paul and Rita Gordon, Frederick County, Maryland: A Playground of the Civil War(The Heritage Partnership, Frederick, MD: M&B Printing Inc., 1994), 25-34.

Kennedy Farmhouse

2406 Chestnut Grove Road SharpsburgMD21782 (202) 537-8900 http://www.johnbrown.org/toc.htmThe Kennedy Farmhouse was used by John Brown and his followers as a staging area for his October 17, 1859 raid on the nearby U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry,Virginia. In July 1859, John Brown, using the pseudonym Isaac Smith, rented the Kennedy farmhouse from the heirs of Dr. Robert Kennedy. Located in southern Washington County,Maryland, Brown used the farmhouse to store arms and supplies, to shelter his followers and to plan his raid on the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, which was only about five miles away. In addition to Brown, at one time twenty-two people occupied the house, including a daughter, a daughter-in-law, two sons, and eighteen other men, five of whom were African Americans. The raid was launched late onOctober 16, 1859and was put down two days later when U.S. Marines stormed the firehouse into which Brown and his raiding party had taken refuge with their hostages. After the raid, a search of the Kennedy Farmhouse uncovered additional arms, maps and letters that revealed the extent of Brown’s plans and the identity of some of his supporters in the North. After passing through the hands of many owners, in 1950 the National Negro Elks purchased the Kennedy Farmhouse, hoping to restore it and open a museum in the house. Unable to raise the necessary funds, the property was sold in 1966. In 1972 South T. Lynn leased the property for a year, and then he and three others bought it. Over the years that followed, Lynn and the late Harold Keshishian bought out the interest of the other two owners. The property was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1974, which provided opportunity to acquire funding to restore the building. Utilizing funds from a number of sources, the farmhouse was fully restored under the direction of the Maryland Historical Trust.

See these sources and websites for additional information: http://www.johnbrown.org/toc.htm

John Brown’s Raid, National Park Service History Series, 2009.

Tony Horwitz, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War, 2012.

National Historical Landmarks summary: http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=1339&ResourceType=Building

Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md0587 MarylandInventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-III-030 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Civil War Trails marker: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=20735&Result=1 Other markers: http://www.hmdb.org/Marker.asp?Marker=1988

Killiansburg Cave

Mile 75.61 of C&O Canal, roughly 1 mile downriver from Snyder’s Landing Road Sharpsburg, MD 21782Some of Sharpsburg’s civilians took shelter in this cave during the Battle of Antietam. Before and during the Battle of Antietam, some residents of Sharpsburg took shelter in the caves in the hillsides above the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. One of those caves, the Killiansburg Cave, was shown in a contemporary drawing after the battle. The cave is located near the Potomac River about two miles west of Sharpsburg.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Charles Adams, The Civil War in Washington County, Maryland – A Guide to 66 points of Interest(Shepherdstown, WV: Charles S. Adams, 1996), 22.

Landon House

3401 Urbana Pike Urbana, MD 21704Landon House was occupied by Northern and Southern troops during the war, and was the site of a ball hosted by J.E.B. Stuart in September 1862. Landon House was reportedly constructed in 1754 as a silk mill – in Fredericksburg, Virginia, along the banks of the Rappahannock River. It was moved to its present location in 1846 by Reverend R.H. Phillips, who then turned it into the Shirley Female Seminary by 1850. During the mid-1850s it became the Landon Military Institute, but by the end of the 1850s was once more a girls’ school, the Landon Female Academy. After the Confederate Army invaded Maryland in September 1862, General Longstreet’s soldiers stayed in the house and on the grounds. Many of them inscribed their names and units, as well as derisive comments about the North, on the walls of the house. On September 8th, 1862, Landon House was the site of General J.E.B. Stuart’s “Sabers and Roses” ball. The dance was the idea of several young ladies from the area, and the amiable Stuart agreed that it would give his men a respite from the stresses of military life. Unfortunately, the festivities were marred by a nearby skirmish between a Federal patrol and a Southern outpost. Though the fight was quickly over, the ball ended as the casualties were brought back to Landon, to be nursed by the female attendees.A little over a week later, on September 16th, Union troops used the recently vacated building as a resting place on their pursuit of the Confederates. Seeing the Southern soldiers’ graffiti, the Union soldiers added their own names, cartoons, and commentaries on the South. (The graffiti is still present on the walls of the house.) After the war, Landon was bought by Colonel Luke Tiernan Brien, a chief of staff to J.E.B. Stuart during the war. It is now privately owned, and occasionally used for special events.

See these sources and websites for additional information: https://sites.google.com/site/landonhousecom/historyhttp://www.freewebs.com/landonhouse/index.htm

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (enter F-7-003 in “Site No.” in “Search by Property” tab)

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=283&FROM=NRMapFR.htmlCivil War Trails Marker: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=1739

Monocacy National Battlefield

5201 Urbana Pike Frederick, MD 21704 (301) 662-3515 http://www.nps.gov/monoUnion and Confederate forces clashed here on July 9, 1864, in the “Battle that Saved Washington. “In the summer of 1864, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was pinned down in Petersburg, VA by Union forces. In hopes of relieving pressure by diverting part of the Union army, General Robert E. Lee sent General Jubal Early up the Shenandoah Valley and into Maryland. Early entered Maryland through Washington County and continued east towards Washington, DC. After demanding ransom from the towns of Hagerstown and Middletown, Early’s forces reached Frederick on July 8. On July 9, the city of Frederick was also ransomed, and Early moved westward towards the Monocacy River. He was met there by a force of Union soldiers, led by General Lew Wallace, perhaps half the size of the Confederate army. Wallace, not sure whether Early was aiming for Baltimore or Washington, was forced to guard three miles of the Monocacy River against either outcome. The ensuing battle ended in a Union retreat, but it delayed Early long enough to allow for additional Union forces to arrive to protect Washington.The park includes several historic residences and other structures, and there are five historic monuments on the battlefield.

See these sources and websites for additional information: Monocacy National Battlefield website: http://www.nps.gov/mono

Monocacy National Battlefield Staff, The Battle of Monocacy, July 9, 1964[Handbook] 2010. Brett W. Spaulding, Last Chance for Victory: Jubal Early’s 1864 Maryland Invasion, 2010.

National Historic Landmarks summary: http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=687&ResourceType

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=208&FROM=NRMapFR.html

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter F-3-42 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Civil War Sites Advisory Commission’s Battle Summary for Monocacy: http://www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/md007.htmCivil War Trust: http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/monocacy.html

Mt. Olivet Cemetery

515 South Market Street Frederick, MD 21701Many Union and Confederate soldiers are buried in this cemetery, as well as Barbara Fritchie and other Civil War notables. Mt. Olivet Cemetery was created in 1854, seven years before the beginning of the Civil War. Many soldiers killed in nearby battles and those who died in the military hospital in Frederick were originally buried in Mt. Olivet. Most of the Union soldiers were moved to Antietam National Cemetery after the war, and many of the Confederate soldiers were retrieved by relatives or reinterred in Confederate cemeteries, such as Rose Hill in Hagerstown. But a few Union soldiers killed in the war and many veterans from the Frederick region are buried in Mt. Olivet, and many Confederate soldiers killed in area battles were reinterred here in 1880 by the Frederick Chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy. Many of these soldiers were unknown and were buried in a mass grave, but the gravestones of other Confederate soldiers form a long line on one side of the cemetery. A Confederate monument was erected near these graves in 1881. Barbara Fritchie, immortalized in John Greenleaf Whittier’s famous poem, is also buried in Mt. Olivet.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Frederick County, Maryland – A Guide to 49 Historic Points of Interest(Shepherdstown, WV: The Author, 1995): 17.

National Museum of Civil War Medicine

48 East Patrick Street Frederick, MD 21701 Contact: 301-695-1864 http://www.civilwarmed.orgThe museum tells the story of medical care for soldiers during the Civil War. The National Museum of Civil War Medicine tells the fascinating story of the evolving medical treatment of soldiers during the Civil War. The sheer number of casualties overwhelmed available resources, leading by necessity to advancements in battlefield triage, ambulance service, operations, the quality of nursing care, and in other areas of medical care. The building in which the National Museum of Civil War Medicine resides was once the furniture shop of James Whitehill as well as his undertaking business during the war.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

National Museum of Civil War Medicine website: http://www.civilwarmed.org

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Frederick County, Maryland – A Guide to 49 Historic Points of Interest (Shepherdstown, WV: The Author, 1995), 13

Philip Pry House (Pry Farm)

18906 Shepherdstown Pike (MD 34) Keedysville, MD 21756This farm was used by General George McClellan as headquarters during the Battle of Antietam; it was also a hospital and signal station. The Philip Pry House dates back to July 1844. Standing on a hill, it commands a good view of the Antietam battlefield, leading Union General George McClellan to make his headquarters there during the Battle of Antietam. The location also served as the medical headquarters of Dr. Jonathan Letterman, who put into place influential plans reorganizing the army medical system while here; both the barn and the house were called into service as hospitals. General Israel B. Richardson, “the Union hero of Bloody Lane,” died here on November 3rd, after being visited by President Abraham Lincoln in October. Today, the Pry House is part of Antietam National Battlefield and serves as a field hospital museum for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

See these sources and websites for additional information: http://www.civilwarmed.org/VisitUs/PryHouse.aspxhttp://www.nps.gov/anti/planyourvisit/pryhouse.htm

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1084; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1083;http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1082

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0355 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Washington County, Maryland – A Guide to 66 points of Interest (Shepherdstown, WV: Charles S. Adams, 1996), 12.

Prospect Hall

889 Butterfly Lane Frederick, MD 21703 (301) 662-4210Prospect Hall was the site of the transfer of command of the Army of the Potomac from Union General Joseph Hooker to General George Meade before the Battle of Gettysburg. Prospect Hall was built during the early 19th century, possibly as early as the late 18th century, with several later additions and alterations to its structure.During the Civil War, it was the home of Colonel William P. Maulsby, the commanding officer of the First Regiment of the Potomac Home Brigade. Stephen Douglass, the Democratic candidate for the 1860 presidential election, is known to have visited here. In 1862, Confederate troops camped at the Hall prior to the Battle of South Mountain. On June 28, 1863, just days before the Battle of Gettysburg, Union General George G. Meade assumed control of the Army of the Potomac on the grounds of Prospect Hall, relieving General Joseph Hooker.During the winter of 1861-62, Colonel and Mrs. Maulsby hosted a ball at Prospect Hall. One of the guests, Septima Collis, the wife of a Union general, described the event:

The pièce de résistance of the season, in the way of amusement, was a ball given by Colonel and Mrs. Maltby [Maulsby], who lived in the suburbs of the town. The Colonel, if I remember rightly, then commanded a Maryland regiment or brigade. Their very large and well appointed residence was admirably adapted to gratify the desire of our hostess to make the occasion a memorable one; the immense hall served as the ballroom; the staircases afforded ample sitting room for those who did not participate in, or desired to rest from, the merry whirl, while the ante-rooms presented the most bountiful opportunities of quenching thirst or appeasing appetite. I shall never forget one little French lieutenant who divided his time with precise irregularity between the dance and the punch-bowl, and whose dangling sabre, in its revolutions in the waltz, left as many impressions upon friends as it ever did upon foes; yet it had the happy effect of giving the gentleman and his partner full possession of the field, whenever he could prevail upon some enterprising spinster to join him in cutting a swath through the crowd.”

Prospect Hall now houses a private school.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter F-3-061 in search box to right of “Site No.”) Septima M. Collis, A Woman’s War Record 1861 – 1865 (New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1889), 9-10.

Civil War Trails Historical Marker: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=2775

Ramsey House

119 Record Street Frederick, MD 21701In October 1862, Abraham Lincoln stopped at this house to visit a Union general recovering from a wound received at the Battle of Antietam. In October 1862, after the Battle of Antietam the previous month, President Abraham Lincoln made a surprise visit to the site of the battle and to Union General George McClellan, whose army was camped in the vicinity. On his return to Washington, Lincoln traveled to Frederick to take a train back to the capital. He first stopped at the home of Mrs. Ellen Tyler Ramsey, where Union General George Hartsuff was recuperating from a wound he had received at Antietam. President Lincoln was then driven to the train station where he gave a brief impromptu speech before boarding the train. The house is now a private residence.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Frederick County, Maryland – A Guide to 49 Historic Points of Interest(Shepherdstown, WV: The Author, 1995): 15

“The President’s Visit to McClellan’s Army,” Harper’s Weekly, October 25, 1862, 684, 686.

“President Lincoln Stopped Off Here On Way Back From Antietam Battlefield,” Frederick News, September 1, 1961, 19. Historical Marker Database: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=2818

Roger Brooke Taney House

121 South Bentz Street Frederick, MD 21701 Contact: Historical Society of Frederick County http://www.hsfcinfo.org/taney/index.htm 301-663-1188This house was owned by Roger Brooke Taney, future Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, from 1815 to 1823. Roger Brooke Taney began his career as a lawyer in Frederick, MD, and practiced law there between 1801 and 1823. He owned this house from 1815 to 1823. Taney later became Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, and was the chief author of the infamous Dred Scott case in 1857, in which Taney “affirmed” that African Americans “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The Dred Scottcase was one of the catalysts of the Civil War. Taney and Abraham Lincoln also clashed in 1861 over the arrest of John Merryman in Baltimore by military authorities. Taney claimed the military had no right to hold Merryman without a judicial inquiry, but Lincoln claimed the Constitution gave the President extra-legal authority in times of war. The Roger Brooke Taney House is now operated by the Historical Society of Frederick County as a museum featuring items of interest from the lives of both Taney and his brother-in-law Francis Scott Key. Taney is buried in Frederick, in St. John’s Catholic Church Cemetery.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md0338

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter FHD-1008 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Charles S. Adams, The Civil War in Frederick County, Maryland – A Guide to 49 Historic Points of Interest(Shepherdstown, WV: The Author, 1995), 7

Susan Cooke Soderberg, A Guide to Civil War Sites in Maryland – Blue and Gray in a Border State(Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, 1998), 90.

Sharpsburg Town Square

Main and Mechanic Streets Sharpsburg, MD 21782The United States government authorized the enlistment of African Americans for the Union Army in 1863, but it was the Spring of 1864 before active recruitment began. A company of the 19th Regiment of the USCT (United States Colored Troops), created with Maryland soldiers, was dispatched on a recruiting mission to western Maryland in April 1864. In Sharpsburg, the soldiers headquartered in the Methodist Church. According to a complaint by townspeople sent to the Union military commander for the region, the USCT did not bother to differentiate between free or enslaved African Americans in their recruitment efforts. One local farmer, Henry Piper, complained that one of his slaves, Jeremiah Summers, only 16 years old and therefore underage, had been kidnapped by the USCT recruiters. When he tried to retrieve Jeremiah, he was roughed up and arrested by the soldiers in the main square in town. Piper and his fellow townspeople claimed that they were all very loyal to the Union, proven in part by the fact that they had voted 329 to 2 in favor of Maryland’s effort to emancipate slaves in the state, and that the citizens of Sharpsburg felt “aggrieved and outraged” by the behavior of the USCT recruiting party. Jeremiah Summers was eventually returned to Piper. Summers’s view of the recruiting episode has been lost to history.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Letter, John Miller, Sharpsburg, to Major General L. Wallace, Baltimore, April 13, 1864, in Maryland Manuscripts, University of Maryland Libraries, Archives and Manuscripts Department, Series 15.5, Box 1, Folder 1, Items 2381 and 2382, in the collection of the Catoctin Center for Regional Studies, Frederick, MD.

St. John the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church and Cemetery

116 East 2nd Street Frederick, MD 21701 (301) 662-8288The church building was used as a hospital during the war, and the cemetery holds the remains of Roger Brooke Taney and several Civil War soldiers. St. John’s Catholic Church, dating to 1837, was used as a hospital during the Civil War. The church was used specifically for the care of Confederate wounded, and an unsubstantiated story attributes that to the church’s high windows hindering any escape attempts.St. John’s Cemetery is one of the rare examples in which the graves of Confederate soldiers, Union white soldiers, and Union African American soldiers co-exist. [There is one grave of an African American soldier, George Washington, who served with the 23rdU.S. Colored Infantry. Before the war, he worked at the nearby Jesuit Novitiate.] Also buried in the cemetery is Roger Brooke Taney, Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.stjohn-frederick.org/aboutus.asphttp://www.stjohn-frederick.org/stjohncemetery.asp

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md0335Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter FHD-0744 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

St. Mark’s Episcopal Church

18313 Lappans Road Boonsboro, MD 21713 www.stmarkslappans.org (301) 582-0417The church was used as a hospital after the Battle of Antietam. St. Mark’s Church was constructed and consecrated in July of 1849. During the Civil War, it was a hospital for wounded men, some of whom were later transferred to local farms to recover. The church held no services from mid-September through November 21st, 1862, reportedly because of battle damage.

See these sources and websites for additional information: http://www.stmarks-lappans.ang-md.org/

National Register of Historic Places summary: http://mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=1219&COUNTY=Washington&FROM=NRCountyList.aspx?COUNTY=Washington

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0024 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Soldiers’ National Cemetery

Gettysburg National Military Park 1195 Baltimore Pike Gettysburg, PA 17325 Contact: (717) 334-1124 ext. 8023 http://www.nps.gov/gettThis cemetery in Gettysburg National Military Park holds the remains of 3,555 Union soldiers. After the Battle of Gettysburg, burials began immediately in what would become the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. The cemetery was dedicated in November of 1863, the occasion of President Abraham Lincoln’s famous “Gettysburg Address.” The cemetery contains 3,555 Union graves (as well as graves of U.S. soldiers from other wars), arranged in a circle to face a central monument. That monument was erected in 1869, and features marble representations of war, peace, liberty, history, and plenty. The Soldiers’ National Cemetery became part of the larger national cemetery system in 1872. William Saunders’ original plan for the cemetery separated it from the battlefield, to be a place of contemplation in which to tell the story of the soldiers’ sacrifice. However, as roads were established through the grounds leading to the battlefield, the effect shifted from one of “destination” to one of “transition.” The cemetery was closed to burials in 1971, and closed to traffic in 1989.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.nps.gov/gett http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/travel/national_cemeteries/Pennsylvania/Gettysburg_National_Cemetery.html

South Mountain State Battlefield

6620 Zittlestown RoadMiddletown MD 21769 http://www.dnr.state.md.us/publiclands/western/southmountainbattlefield.asp 301-791-4767South Mountain State Battlefield preserves and commemorates the various sites associated with the Battle of South Mountain, fought on September 14, 1862. The Battle of South Mountain was the first major Civil War battle in Maryland. The Confederate Army under General Robert E. Lee crossed the Potomac River in early September 1862. Lee established a base in Frederick, and when the Union Army under General George McClellan advanced from the east, Lee devised a bold but risky plan to divide his army and move westward. In one of the oddest breaks in military history, a Union soldier found a discarded copy of Lee’s orders (the famous Special Orders 191) and the usually overly-cautious McClellan led his army in pursuit. Caught off-guard by McClellan’s movement, the Confederates were forced to fight a delaying action on the top of South Mountain to give the divided army time to regroup. The battle, on October 24, 1862, was actually fought in three places – Turner’s and Fox’s Gaps between Middletown and Boonsboro, and Crampton’s Gap to the west of Burkittsville. The battle was a Union victory, but not before Confederate General Stonewall Jackson had captured Harpers Ferry and 12,000 Union soldiers, and the Confederate Army had reconsolidated itself in preparation for what would become the Battle of Antietam.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.dnr.state.md.us/publiclands/western/southmountainbattlefield.asp

Civil War Sites Advisory Commission’s Battle Summary for South Mountain: http://www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/md002.htm

Civil War Trust: http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/south-mountain.html

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

209W. Main Street(MD 34) Sharpsburg, MD 21782 (301)432-7089 http://www.stpaulssharpsburg.org/index.htmlSt. Paul’s Episcopal Church of Sharpsburg was badly damaged during the Battle of Antietam, and was used as a hospital by both the Confederate and Union armies. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church of Sharpsburg was organized in 1818. The cornerstone of the two-story stone, stuccoed, building was laid onMay 31, 1819. During the September 17, 1862 Battle of Antietam the church was badly damaged and was subsequently abandoned as a place of worship. On the day of the battle and the day following, the Confederates used the church as a hospital. Most of the furnishings were removed to make room for beds. Some of those who died were buried in the church’s cemetery, although their remains were later removed to the Washington Cemetery in Hagerstown, Maryland. After the Confederates retreated, the Union army used the church as a hospital as well. Following the war, the church raised funds to rebuild. The second cornerstone was laid onOctober 30, 1871, and using the original stone and bell, the new church was completed in 1874. Improvements to the structure were made in 1965 and 2000. See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.stpaulssharpsburg.org/History.htm

Vernell Doyle and Tim Doyle, Sharpsburg, Images ofAmerica Series, 2009.

MarylandInventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0517 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Tolson’s Chapel

111 East High Street Sharpsburg, MD 21782 http://www.tolsonschapel.org E-mail: tolsonschapel@gmail.comTolson’s Chapel was an African American church and Freedmen’s Bureau school in the years after the Civil War. In September of 1862, residents of Sharpsburg witnessed the bloodiest single day of the Civil War, the Battle of Antietam. The Union Army could claim only a partial victory that day, but it was enough to give President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had awaited to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. For many Americans thereafter, especially for the almost four million held in bondage, the war was about freedom.After the war, and practically on the battlefield that spurred Lincoln’s call for emancipation, the small African American community of Sharpsburg began work on a church. Many in this community had been enslaved until 1864, when a new Maryland state constitution abolished slavery. Two years later, in October 1866, the cornerstone of Tolson’s Chapel was laid. This tiny church on a back street in Sharpsburg became the spiritual and educational center of a vibrant community of African American families, and a symbol of their struggles and triumphs.Tolson’s Chapel was built on land donated by Samuel Craig and his wife, both of whom had been free African Americans before the war. The church was built of logs, one story in height, and had an adjoining cemetery. The structure was dedicated in October 1867 as a Methodist church, and named for John Tolson, the first minister.By 1868, Tolson’s Chapel also served as a schoolhouse for local African American children. Responding to the lack of educational facilities for African American children after the war, the federal Freedmen’s Bureau helped local communities throughout the South and in the former border states hire teachers and build schools. The Freedmen’s Bureau helped start at least nineteen schools in Washington and Frederick Counties between 1866 and 1870. In April of 1868, teacher Ezra Johnson opened the “American Union” school in Tolson’s Chapel with eighteen children. In addition to the day school for children, Johnson also began a night school for adults, a Sabbath school, and a temperance organization.The “American Union” school continued until 1870, when Congress began dismantling the Freedmen’s Bureau. By 1871, the state of Maryland began oversight of African American education, and Tolson’s Chapel continued to serve double duty as a school until 1899, when Sharpsburg’s first African American schoolhouse was built nearby at the end of High Street. The last member of Tolson’s Chapel passed away in the 1990s, and the building and cemetery are now under the care of Friends of Tolson’s Chapel. The chapel is open by appointment.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Friends of Tolson’s Chapel website: www.tolsonschapel.org

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1676

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0702 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

War Correspondents Memorial Arch

Gathland State Park 900 Arnoldstown Road Burkittsville MD 21718 Phone: 301-791-4767This elaborate arch was designed to commemorate the journalists and artists of the Civil War. George Alfred Townsend, the youngest war correspondent of the Civil War, became a novelist after the war. While researching one of his books, he discovered the Burkittsville area in Frederick County and constructed a house, “Gapland Hall,” in Crampton’s Gap overlooking the town. Crampton’s Gap was where part of the Battle of South Mountain was fought. While living at Gapland, he designed this memorial to his fellow war correspondents and artists who had depicted the Civil War. The arch was dedicated on October 16th, 1896. The memorial is now part of Gathland State Park, but is maintained by the National Park Service.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) documentation: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.md1322

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-III-117 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

http://www.dnr.state.md.us/publiclands/western/gathland.asphttp://www.nps.gov/anti/historyculture/mnt-arch.htmHistorical Marker Database: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=13977

Washington Confederate Cemetery (within Rose Hill Cemetery)

600 South Potomac Street Hagerstown, MD 21740 http://www.rosehillcemeteryofhagerstown.org/ (301) 739-3630Washington Confederate Cemetery, a section within Hagerstown’s Rose Hill Cemetery, holds the remains of 2,468 Confederate soldiers, mostly unknown, killed in the Antietam, South Mountain, and other battles. When work began on Antietam National Cemetery in 1866, trustees of the cemetery refused to permit Confederate reburials. In 1870, after several years of negotiation and fundraising, the Maryland General Assembly established the Washington Confederate Cemetery, a “cemetery within a cemetery” on the western perimeter of Hagerstown’s Rose Hill Cemetery. After several more years of work, it was dedicated on June 12th, 1877. Nearly 2500 Confederate soldiers killed in the battles of South Mountain and Antietam were exhumed and re-buried here, arranged in a half-circle radiating out from the “Hope” statue in the center. Less than 400 of the remains were able to be identified.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://www.rosehillcemeteryofhagerstown.org/index_files/Page616.htm

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-HAG-183 in search box to right of “Site No.”)

Civil War Trails Historical Marker: http://www.hmdb.org/Marker.asp?Marker=44898

Washington Monument

6620 Zittlestown Road Middletown MD, 21769 (301)791-4767 http://dnr.maryland.gov/publiclands/western/washington.aspWashington Monument was used as a Union signal station before and during the Battle of Antietam, and during the Confederate retreat from Gettysburg. Although other monuments to the memory of George Washington were begun at an earlier date, this monument was the first to be completed. The monument was begun on July 4, 1827 by the citizens of Boonsboro, Maryland and the surrounding region. When it was completed in September, the monument stood thirty feet high on a fifty-four foot circular base. By the time of the Civil War, however, vandals and mischievous boys had tossed eight to ten feet of stone from the monument down the mountainside. On September 15, 1862, following the Army of the Potomac’s seizure of the passes through South Mountain, a Union signal station was established on Washington Monument. Signal officers there detected the Confederate army passing along the road from Sharpsburg to Shepherdstown and the beginnings of a thin battle line beyond Antietam Creek. During the September 17 Battle of Antietam, the signal officer at Washington Monument was ordered to watch for enemy movements from Pleasant Valley or the Potomac. On July 8, 1863, during the Gettysburg Campaign, a Union signal station was again established atopWashingtonMonumentand reported Confederate movements during the Battle of Boonsboro, which took place that day. In 1882, through the efforts of theSouthMountainencampment of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows and Madeleine Dahlgren, who lived at the Mountain House at Turner’s Gap, and who was the widow of Civil War naval officer John A. Dahlgren, a fund was established to rebuild the monument. Repairs were made and for the first time a carriage road was constructed to the monument. Within twenty years, however, a fissure had opened in the monument and it soon fell into ruins. In 1922 the monument and one acre of surrounding land were purchased by the Washington County Historical Society. From 1934 to 1936, the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Depression-era agency created to alleviate national unemployment, rebuilt the monument. The property was donated to the state ofMarylandin 1934 and is presently a state park.

See these sources and websites for additional information:

http://dnr.maryland.gov/publiclands/western/washington.asp

J. Willard Brown, The Signal Corps, U.S.A., in the War of the Rebellion, 1896.

MarylandInventory of Historic Properties: http://www.mdihp.net/ (Select “Search by Property” tab, and enter WA-II-0501 in search box to right of “Site No.”)