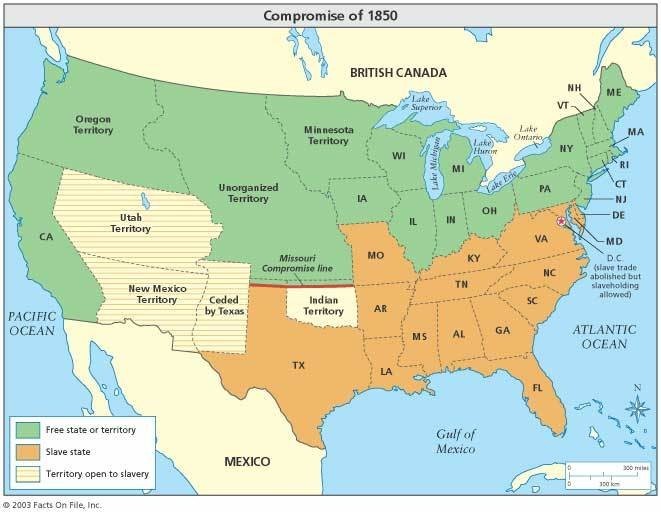

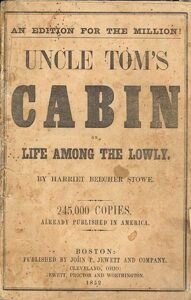

Throughout the decade of the 1850s, mid-Marylanders and their near-by neighbors in Pennsylvania and Virginia found themselves trying to navigate a path through the increasingly tense sectional disagreements between the North and the South. Residing in a non-slaveholding state, most Pennsylvanians aligned themselves with the Northern position. For opposite reasons, most Virginians on the Potomac River border saw themselves entwined with Southern policies. Mid-Marylanders, on the other hand, had extensive ties – politically, economically, and socially – with both the North and the South. As sectional discord became more difficult to contain, citizens in this border region became witnesses to, and participants in, some of the most cataclysmic events that preceded the outbreak of war. By 1861, these border residents were faced with difficult, at times agonizing, choices as the country lurched toward war.

Slavery and the Growth of Sectionalism

Raid on Harpers Ferry

In June 1859, a man calling himself Mr. Stearns appeared in Frederick County, ostensibly selling books but in reality familiarizing himself with the area. He reported the information he gathered to a Mr. Isaac Smith, who in July rented the Kennedy farm in the southeastern corner of Washington County. Local citizens paid little attention to Stearns or to Smith, or to any of Smith’s twenty-one associates, five of whom were Black. They did not suspect that Smith was actually abolitionist John Brown, who was formulating a plan to seize the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry and to incite a slave insurrection.

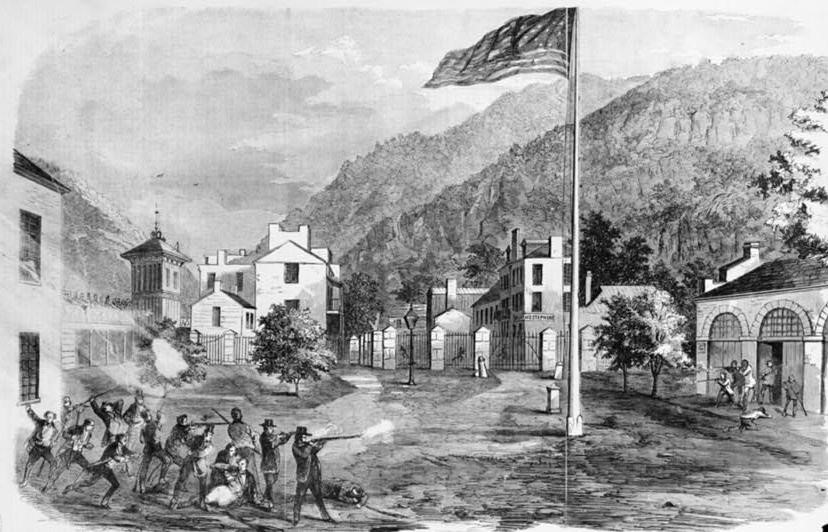

On October 17, 1859, Jacob Engelbrecht noted that in Frederick at 10:00 a.m. bells wereringing with commands for the town’s militia companies to assemble for the purpose of suppressing “a kind of Insurrection among the Negroes of Jefferson County Va … to Sieze on the u.s. arms there.” News of a raid at Harpers Ferry quickly set off a wave of panic and confusion in the region. Rumors circulated that there was a force of one thousand insurrectionists, that six hundred armed slaves were John Brown’s Harpers Ferry Raid in 1859 galvanized public opinion on the issue of slavery and led to a hardening of positions North and South. (Library of Congress) participating, and that hundreds of abolitionists had joined the raiders. Frederick’s three military companies, the United Guards (commanded by Captain Thomas Sinn), the Junior Defenders (led by Captain John Ritchie), and the Independent Riflemen (under the command of Captain Ulysses Hobbs), hurried to Frederick’s railroad depot to get to the scene of the “Harpersferry [sic] Riot.” Brig. Gen. Edward Shriver, a Frederick attorney and commander of the Sixteenth Regiment, Maryland Militia, was in overall command of the troops from Frederick. Militia companies from all over the region were already in Harpers Ferry, and the Frederick men joined the others in position around the perimeter of the armory buildings where Brown’s men had taken refuge. There they discovered that the “riot” they were suppressing consisted of twenty-two men, and that many were already dead or in custody. In a report dated October 22, 1859, General Shriver described what happened next:

Between 11 and 12 Oclock [sic] Capt Sinn who was with a detachment of his company on guard in front of the building occupied by the Insurgents was hailed and invited to approach it for the purpose of conference in regard to the terms on which the Insurgents proposed to surrender…. Capt Sinn communicated with me and … I held a parly [sic] with Captain Brown and the gentlemen he held as prisoners…. I told him that he was completely surrounded by an overwhelming force and every avenue of escape effectually guarded.

The raid ended the next day when the brick firehouse where Brown and his men and hostages had taken refuge was stormed by U.S. Marines, led by Col. Robert E. Lee. By 2:45 p.m. the three militia units returned to Frederick from Harpers Ferry.

Although little had actually happened – the slave insurrection never materialized, the raiders were killed or captured, and Brown was summarily hanged – John Brown’s Raid had an enormous effect on the region and the nation. A week after the raid, a Hagerstown paper reported that “the citizens have not yet recovered from their astonishment at the civil war which has so suddenly been engendered in their peaceful community.” Brown’s “nefarious scheme” for the violent overthrow of slavery threatened the region’s stability. In Hagerstown, “the people of our quiet town could hardly realize the fact that a plot of such villainy could have been concocting almost in their midst” by “a few phrenzied [sic], malignant out-laws.” Brown’s antislavery violence was the result, the Hagerstown paper declared, of the “intense fanaticism” of “misguided … abolitionists from the North and elsewhere.” The raid “spread dismay and terror” among Marylanders who feared violent reactions among the state’s large slave and free black populations.

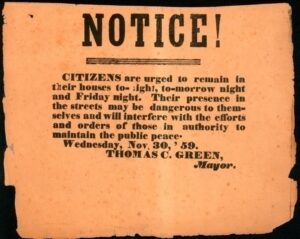

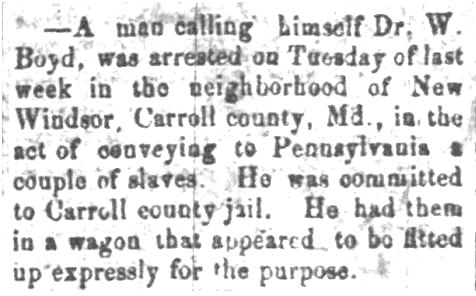

Reaction was similar throughout the region. Following Brown’s raid, rumors spread that another revolt was imminent. Residents of the region became anxious about secret abolitionist plots, about strangers, and even about provocative language. By order of Governor Hicks of Maryland, sheriffs in mid-In this broadside, residents of Charlestown, Virginia (later West Virginia) are urged to stay indoors before the hanging of John Brown. (Gettysburg National Military Park)Maryland were authorized to “arrest and detain” suspicious persons, and they hired extra deputies to assist with the process. In New Windsor, in Carroll County, a Dr. Boyd was arrested for trying to smuggle out of Maryland and into Pennsylvania several slaves who were hidden in a secret compartment he had made in his wagon.

For his effort, Dr. Boyd was incarcerated in the Carroll County jail. A month later, Dr. Breed, a Democrat, was arrested a held for $2,000 bail. He had used “incendiary language, by saying ‘that the negroes ought to murder their masters, kill their wives, set fire to their houses, and then run away by the light of the fire’ and that ‘he thought it was the duty of every Christian to encourage the negroes in it.’”

Brown’s raid exacerbated racial tensions for blacks as well as whites. Among Brown’s personal papers was a letter he wrote in which he referred several times to Thomas Henry, a black clergyman in Hagerstown. Henry had been “long suspected of an improper intercourse and intimacy with the abolitionists of the North.” By November of 1859, the Hagerstown Herald reported that Henry had sold all of his property and left Maryland.

Increased anxieties as a result of the John Brown raid led to the formation of even more militia companies in the region. On January 11, 1860, the Hagerstown newspaper, The Herald of Freedom and Torch Light, noted:

Since the Brown foray, a large number of military companies have been organized in Maryland and Virginia. Nearly every exchange that we open, from the surrounding counties in this and our neighboring State beyond the Potomac, speaks in flattering terms of the formation of one or more of these companies in its midst; and at no former period does there appear to have been so ardent a military spirit awakened.

By February 1, 1860 at least seven new military companies had been formed in Frederick County; in Berkeley County, Virginia, eight companies were formed. Maryland’s arsenal ran out of rifles and muskets to distribute to the new volunteer companies. Even the state’s allotment of weapons for 1860 was already committed by December 24, 1859, and the General Assembly’s appropriation of $70,000, which was much larger than usual, was insufficient to meet the demand from the newly formed military companies.

With the community “excited … to a degree hitherto unknown,” the partisan opportunities that John Brown’s Raid created were seized upon by Democrats in the region, who made the most of the intensified fears by accusing the Republican Party of being in league with John Brown. Although the majority of Republicans continually tried to distance themselves from Brown, portraying him as a solitary figure who acted alone, some mid-Marylanders were no longer listening. While most Northerners saw John Brown as a fanatic who deserved his punishment, John Brown and revolutionary violence were now forged together with the Republican Party in Southern minds. Rather than seeing the raid as an utter failure, those sympathetic to the Southern point of view saw it as a taste of what was to come.

Slavery and Freedom in 1860

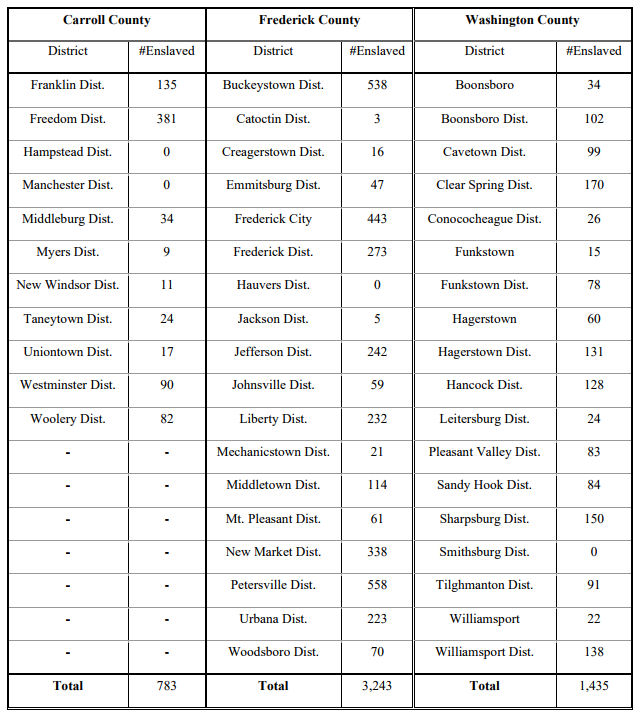

By 1860, the situation of African Americans in mid-Maryland and the surrounding region varied. Slavery in mid-Maryland had been declining since 1820: in 1820 over 16% of the total population of Frederick County was enslaved; by 1860 that number had dropped to 7%. The same pattern was true for Washington County, which went from 14% enslaved in 1820 to 5% in 1860. In Carroll County, created in 1837, only 3% of its residents were enslaved by the time of the Civil War. A prominent historian has argued that in this wheat-producing interior of the state, a way of life was developing in which slavery was “tangential.” Yet these diminishing numbers are in some ways misleading with regard to slavery’s significance in the region, for slavery persisted in exerting its influence politically and socially despite its decline. Mid-Maryland was not economically dependent on slavery, but it did have an investment in the institution.

1860 US Census Enumeration of Enslaved African Americans by County and District

The neighboring counties in Pennsylvania and Virginia had demographic patterns distinct from those in mid-Maryland. Pennsylvania was a non slaveholding state by 1860. In that year, Franklin and Adams Counties had small free Black populations of 1,799 and 474, respectively, which together comprised a little over 3% of the total population of the two counties. In Loudoun County, Virginia, on the other hand, where slavery was still a thriving institution, African Americans made up 25% of the total population, and the vast majority were enslaved. A similar pattern existed in Jefferson County, Virginia, where African Americans comprised 27% of the population and nearly 9 of every 10 were enslaved in 1860.

It was the growth of the free Black population, which increased faster than any other segment of the population, that was the most notable demographic development in mid-Maryland and across the state throughout the nineteenth century. As slavery declined, the number of free African Americans increased steadily, and by 1860, free African Americans outnumbered those enslaved. In Frederick County, the percentage of free Black individuals rose to 11% of the total population in 1860; in both Washington and Carroll Counties, free African Americans accounted for 5% of the total population in each county. In 1860, the three mid-Maryland counties included almost 8,000 free African American residents navigating a society that exerted social and political pressure to keep them subordinate.

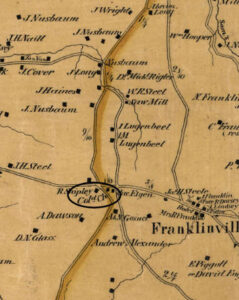

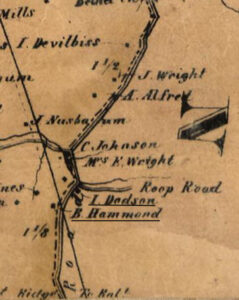

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, free Black families sought the strength of community to lift them through the struggles of life. In the mid-Maryland counties, the county-seat towns of Frederick, Hagerstown, and Westminster, were home to the greatest concentrations of free Black households. They formed communities within – and largely separate from – the larger white population. Similarly, free Black communities developed on the edges of the smaller towns and villages. Scattered clusters of Black households formed in rural countryside, usually where a source of employment – larger farms, mills, iron works – was located nearby. In many cases, these rural groups grew around one or two free Black landowners on whose land other households often related by kinship settled as tenants. Others lived as tenants on nearby properties. While the early city communities often included a church building, in rural areas such institutional buildings were less common and congregations simply gathered in homes or in white churches offered by sympathetic white neighbors.

Hagerstown, the county seat of Washington County, was a busy market town with over 2,600 inhabitants in 1820, 112 of whom were free African Americans and 119 enslaved. In 1818, the Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church was established to serve the free Black and enslaved people of Hagerstown. By 1830, the free Black population in the city had nearly tripled and in 1838, the Ebenezer AME Church congregation was formed. Both the ME and AME congregations built their churches on or near Jonathon Street, in the northwest quadrant of the city, where many of the free Black households were located.

By 1850, the free Black population of Washington County numbered over 1,800 men, women, and children, largely scattered across the rural county. Small clusters of households were located on the back streets of several towns and villages. In Boonsboro, six of the seven Black households were listed in succession on the census. In Williamsport, 35 free Black households appeared in several clusters of 3-5 houses. Approximately 46 free African Americans lived in Sharpsburg by 1860, including a group of related families living on West Antietam Street. They were descendants of Nancy Carter, who purchased one of the lots in 1819. On East High Street (also known as Back Street) several tenant families occupied homes on lots owned by Samuel and Catherine Craig, both formerly enslaved. Other rural towns included small populations of free African Americans, including Clear Spring and Hancock.

The rural hills and mountainsides of Washington County also attracted enclaves of free African Americans. On Red Hill, near Sharpsburg and Keedysville, the wooded land owned by the Antietam Iron Works harbored an early cluster of free Black households. Likely employed at the nearby iron works, two free Black men and one woman were listed as heads of household in the area. By 1830, the number of households had grown to seven. Rev. Thomas Henry noted serving an AME congregation at the iron works in the late 1830s in a log schoolhouse at the base of Red Hill. When the iron works land was sold after the death of the owner in 1856, several lots were purchased by Black families. By 1860, the community included approximately 20 independent households, five of which owned the land on which they lived.

Of note to the west, in the Clear Spring District, was the farm of Nathan Williams, encompassing the ruined walls of the 1750s stone fort called Fort Frederick. Williams purchased the land in 1857. The Williams’ Fort Frederick farm would play a role in the coming Civil War, selling supplies to both Federal troops encamped on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, and to Confederates on the Virginia side.

In Frederick City, Frederick County’s seat of government, the antebellum free Black population was concentrated on the south and east edges of the city. In 1825, the Frederick County tax assessment record listed five Black landowners in “Fredericktown,” including William Hammond. Hammond’s property was likely on All Saints Street, where in 1818, he sold part of Lot 10 to five free Black men, David Peck, Nicholas Smith, James Harper, Archibald Gull, and Sampson Gross. The five men purchased the lot as trustees to “build a house of Worship for the use of the members of the Methodist Episcopal Church.” The church would serve as the center of the Black community on the south side of Frederick. By 1835, the city’s Black landowners had grown to 22, twelve of whom were located on the south end of town along All Saints Street, South Street, and South Market Street. There were also two lot owners on 6th Street and one on 3rd Street, likely in the vicinity of the Bethel (Quinn) AME Chapel, built on East 3rd Street in 1819. Another six Black residents owned lots along East Street, in a section called “Sherb Row” (today’s Shab Row). Eight of the Black lot owners in Fredericktown occupied brick houses, while twelve owners lived in one-story log dwellings. One, Susan Duffin, lived in a “1 story rough cast house” located on “1st St.”

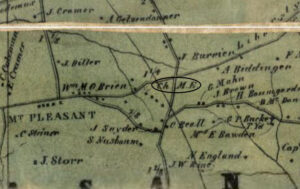

Free African Americans in Frederick County formed communities on the edges of at least six of the county’s rural town/villages. These included Emmitsburg (W. Lincoln Ave., ca.1830), Lewistown (Powell Road, 1840s), Libertytown (1830s), New Market (1830s), Middletown (S. Jefferson St., “Little Africa,” 1820s), and Mt. Pleasant (ca.1856). Significantly, John B. Snowden, a Black resident in the Westminster area (Carroll Co.) noted that he sent three of his children to school in Libertytown, perhaps in the 1840s. It is unclear what school that might have been.

Three Frederick County rural town communities included associated church buildings before 1860. A Methodist Episcopal (ME) Church was indicated on the outskirts of Mt. Pleasant on the 1858 Bond map of Frederick County. The earliest burial in the adjoining cemetery is dated 1856. This early church appears to be in the same location as today’s Silver Hill United Methodist Church, deeded by a local landowner to the trustees of the “Colored People’s Methodist Episcopal Church of ‘Mt. Pleasant’” in 1875. In Lewistown, the “Colored Methodist Episcopal” congregation purchased the former white Protestant Episcopal church building in 1859. In Middletown, the Black Methodist Episcopal congregation built their church as early as 1829. On August 25, 1829, Israel Ramsburg sold a quarter acre of land to Isaac Johnson, Jacob Black, Leonard Maers, Samuel Walker, and Basil Bell, the trustees of the “Methodist Episcopal African Church at Middle Town” (later called the Asbury ME Church) for $50, “that they shall erect thereon a house of Public Worship for the use of the members of the colored people belonging to the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America.”

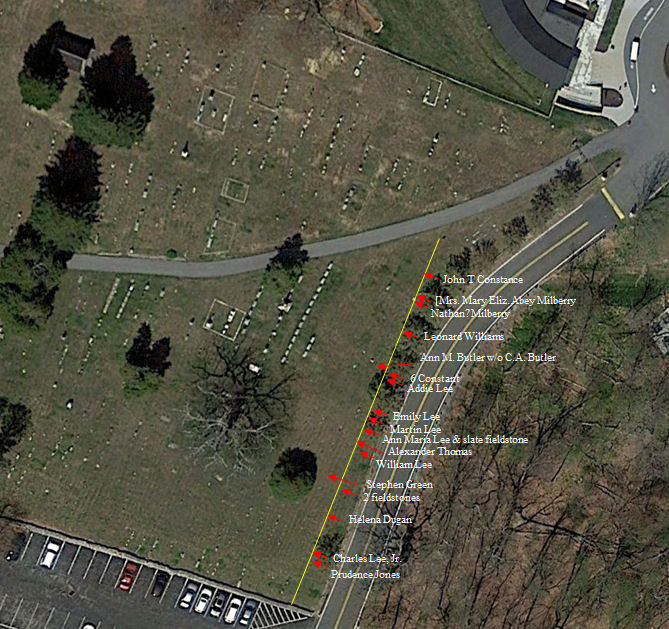

In rural northern Frederick County, the “Mountain Community” was an early cluster of rural free Black households (located on today’s Annandale & Crystal Falls Roads). In 1804, Charles Lee purchased his freedom from John Bayard, a local large landowner and enslaver. Lee bought his first parcel of land in 1813 and owned a second parcel by 1825. Each of the two parcels included a log dwelling in 1825, according to the Frederick County tax record. It is likely Charles Lee occupied one of the lots while his adult son Isaac lived on the other with his young family. This small kinship cluster formed the core of a larger scattered community that grew along the mountain road just north of the area’s largest employer, Mount Saint Mary’s College. In 1835, the county tax assessment record identified Stephen Green with three acres of “mountain land” and a “log house” located in the same area. By 1850, Stephen Green, a “laborer,” was listed in the US Census with his wife Susan and four children, along with Augustus Green, likely Stephen’s brother. “Gust. Green” was additionally listed on the census as a laborer at Mount St. Mary’s College. William Richardson was another free Black employee at the college in 1850. Richardson was listed on the census as the head of a household next to Stephen Green, along with his wife, five children, and a boarder named James Bowie. Richardson’s next neighbor was Martin Conrad, who owned $200 in real estate and lived with his wife and a woman named Mary Lee. Most, if not all of these “mountain community” residents were members of the Catholic Church and many were buried in a segregated section of the nearly St. Anthony’s Cemetery.

As free African American inhabitants of Frederick County grew steadily in number through the first half of the 19th century, many free Black households gathered in rural clusters similar to the “Mountain Community” (described above). A small enclave known as Poplar Ridge (Irishtown Road) formed north of Emmitsburg in the 1820s. Pattersonville (Catoctin Hollow Road) got its start in 1853 when Robert Patterson purchased land on the west side of the mountain (later known as “Bob’s Hill”) near Catoctin Furnace. The Bartonsville community (Bartonsville Road) got its start east of Frederick in 1838; Mt. Ephraim (near Sugarloaf Mountain) began with a land purchase in 1814; and the Burkittsville area community (Route 17/Gapland Rd.) began to coalesce by 1840 when an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) congregation was identified by Rev. Thomas Henry. The congregation purchased a lot in 1858 and constructed a church building soon after.

By the time Carroll County was carved from eastern Frederick County (and western Baltimore County) in 1837, a scattered free Black community had already begun to form along both sides of Buffalo Road, the new boundary line between Frederick’s Liberty District and Carroll’s Franklin District. In 1835, two years prior to the county division, James Smith, a free Black man, was assessed for 12 acres of a parcel of land called Leigh Castle and a “Log House,” then located within Frederick County. Smith was again assessed for his 12 acres of Leigh Castle in 1837, this time in the newly-formed Carroll County, District 9 (Franklin District). It was on part of the tract known as Leigh Castle that the “Colored peoples Church called ‘Fair View’” was constructed on Buffalo Road about 1851. By 1840, the US Population Census recorded 29 free Black households in District 9, including James Smith, as well as Dotson (Dodson), Dorsey, and Murdoc (Murdock) families that would later be noted among the founders of the Fairview ME Church. Other founding church families were listed on the 1840 census in Liberty District (Dist. 8) in Frederick County, including Hammond (Boss, Moses) and Costly. A Fairview Church history also named William Flanagain, Jefferson Carter, Tyler Murdock, and John and Daniel Hammond as early members. The 1850 census records show Jefferson Carter living in Liberty District in Frederick County, while Daniel Hammond (11-year-old son of Moses Hammond) lived in Franklin District in Carroll County. In 1862, the “Cold Ch” on the Buffalo Road boundary between the two districts/counties appeared on Martenet’s map of Carroll County.

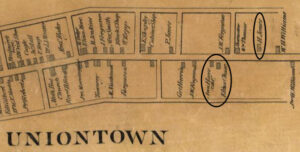

Another rural cluster of independent African Americanhouseholds was located in District 2 (Uniontown District) in Carroll County. The rural district with Uniontown at its center included at least 35 free Black households in the 1840 US Population Census. Among those listed was an elderly woman named “Darky Donson,” who shared her home with a young man and child. By 1850, “Dacus Dunston” (age 80) was listed on the census in her own household with real estate valued at $200, which she shared with the separate household of her son Barney Dunston. In 1858, probably following his mother’s death, Dunston (Dunson) sold the property located on the road “from Uniontown to Middleburg” to Singleton Hughes, a formerly enslaved man and ME preacher.

Hughes reportedly held church services in the former Dunston home and in 1859, sold the property to the trustees of the Methodist Episcopal Church (“colored”), including himself, Jeremiah Key, Ephraim Brown, William [Joabs], William H. Brown, William Matthews, and William H. Dunston. Members of the congregation included a small enclave of free Black residents on the west end of Uniontown. Among them were Dennis and Eliza Chase, who owned their lot as early as 1850 according to the census, Anna Hays, who purchased her lot in 1859, and Perry and Harriet Jones, who owned their lot by 1860.

In the northwestern Taneytown District (District 1) where in 1850 enslaved people far outnumbered free African Americans, a tiny enclave of three independent Black households (16 people) was present in the small town of Taneytown. By 1860, that number had grown to seven households representing 40 free Black men, women, and children. The district was home to St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, which numbered among its members John Coats and family, a free Black man who owned a lot in Taneytown by 1850 and was buried in the church cemetery in 1882. Others gathered for meetings held by Methodist preacher John B. Snowden.

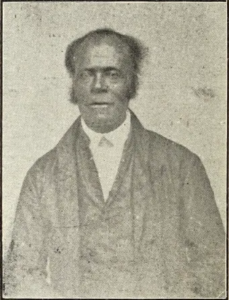

The town of Westminster, Carroll County’s seat of government, was situated in the middle of District 7 (Westminster District). At the time of the 1850 census, 51 free Black individuals resided in the town of Westminster. About half of those lived as servants in white households, while the remaining (24) lived in seven independent free Black households. Beale (Billy) Beho owned 2 acres in “Pigman’s Addition to Westminster,” said to have been purchased by Beho in 1838. It was located on the east side of the road to Littlestown “opposite the property of Isaac Shriver Esq.” where Shriver had laid out a short cross street called Union Street on his 17-acre “Shriver’s Addition to Westminster” in 1834. In 1864, Elizabeth and William Harden were the first African Americans to purchase an unimproved lot on the south side of Union Street. John B. Snowden was already preaching the (Methodist Episcopal) gospel when he purchased his freedom and arrived in Westminster in 1831. In his autobiography, Snowden described holding “protracted meetings in Westminster, my home, for many years” prior to the 1864 formation of the all-Black Washington Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. No schools for African American children were available during this period. Snowden recalled paying a private tutor to teach his children, and was even offered the opportunity to send them to a white school during off-hours:

Mr. John Bowman, who taught a white school near where I lived a few years before the Rebellion, undertook to teach my boys at night, but was stopped by bad young white men, who would slip and fasten the schoolhouse door on the outside and then stone the house. It was not an easy matter to try to have my boys and girls to learn just a little in the State of Maryland in ante-bellum days.

Snowden’s children were the exception to the rule. For those families with access to a church community, Sunday school would provide the only education available.

John Brown believed that only a war against slavery would bring an end to the institution in the United States. Although it would not happen exactly the way he envisioned, it would be war that brought its final demise. For decades enslaved people damaged the institution by successfully fleeing their bonds. In 1862, one Frederick citizen wrote to The Frederick Examiner, “Slave owners see that the institution is melting away like a snow ball in the sun.” The final blow would come in 1863 with President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and his instruction to the US Army to accept free and enslaved volunteers, eventually including Black men in the draft. The influx of highly motivated and determined Black men into the Federal ranks would mark a turning point in the Civil War that brought an end to slavery in the US.

Conclusion

John Brown believed that only a war against slavery would bring an end to the institution in the United States. Although it would not happen exactly the way he envisioned, it would be war that brought its final demise. For decades enslaved people damaged the institution by successfully fleeing their bonds. In 1862, one Frederick citizen wrote to The Frederick Examiner, “Slave owners see that the institution is melting away like a snow ball in the sun.” The final blow would come in 1863 with President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and his instruction to the US Army to accept free and enslaved volunteers, eventually including Black men in the draft. The influx of highly motivated and determined Black men into the Federal ranks would mark a turning point in the Civil War that brought an end to slavery in the US.

Stories in Focus