The Civil War was, as President Lincoln explained in his address to Congress on July 4th, 1861, “essentially a People’s contest.” A Pennsylvania newspaper put it this way:”We are all in this war; those who fight and those who stay at home.” Those who stayed at home in the border region of mid-Maryland became connected to the war in profound ways. Their communities became battlegrounds as armies marched, camped, and fought in their streets and in their fields. They had to cope with the many disruptions this caused: the presence of soldiers, the destruction of property, the regulations imposed by military officials, the sick and wounded men who filled the makeshift hospitals, and the drafting of land, homes, and public buildings into military service. They also had to take sides. As declarations of war were made, citizens with opposing points of view suddenly became enemies. Many would spend four years trying to preserve the Union; for others, it was the Confederacy that upheld their concept of what America meant, and they worked to support it. Maryland would remain in the Union, but deep and bitter divisions existed within the communities and the families of this border region.

Excitement and Alarm

In the spring of 1861 the mid-Maryland border region existed in a state of “excitement” and alarm. The people of Frederick witnessed daily marching by militias, the appearance of federal troops, and, on April 26, the convening of a special session of the state legislature to consider the issue of secession (see section on Civil Liberties). Passions were high, and inflamed still further when, on May 8, the courthouse burned to the ground, allegedly set fire by a Confederate sympathizer. Public discourse became volatile: when Union men persisted in suggesting that Confederate supporters be hanged, the Frederick Herald advised them to remember that “Union shriekers have necks for ropes as well as secessionists, and that secessionists have hands to tie them on.”

Citizens showed their loyalties and confronted their opponents in a variety of ways. They joined militias, held flag-raising events, and asserted the primacy of the Union, or the right to secede, in resolutions published in newspapers that did not conceal their sectional allegiances.

The most famous flag-waver of all, Barbara Fritchie, would wave the Union flag, as the story goes, in September 1862, when Stonewall Jackson and his troops marched by her home on Patrick Street. Similar incidents occurred with other inhabitants asserting their position in front of soldiers. Nannie Crouse of Middletown waved a large Union flag in the presence of Confederate troops, as did Mary Quantrill of Frederick.

Soldiers and Civilians

It was inevitable that significant interaction between civilians and soldiers would take place in the mid-Maryland and surrounding region. Mid-Marylanders had in their midst both Union troops, which occupied the state throughout the war, and Confederate troops, which launched campaigns into the North through mid-Maryland. Since allegiances in this border area were mixed, soldiers on both sides encountered towns and civilians loyal to the Union, and others with loyalties to the Confederacy. At times local allegiances confounded the military officers: when Confederate Maj. Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson threatened to bombard Hancock, Maryland on Jan. 5, 1862, Union Brig. Gen. Frederick W. Lander replied: “… tell him to bombard and be damned. If he opens his batteries on this town he will injure more of his friends than he will of the enemy, for this is a damned sesech place anyhow!” The allegiance of civilians remained a delicate issue throughout the war.

Early in the war, discipline among the soldiers with regard to the civilian population was strong. Confederate troops were careful not to place an undue burden on local citizens; as the Confederacy was still hopeful that the state might provide support and recruits to its army. The Union army maintained order by enforcing rules against plundering while in friendly territory. Union soldiers were required to pay for food and supplies received from private citizens. Sometimes private citizens saw opportunity in the soldiers’ needs and inflated prices excessively. One soldier commented that they could buy almost any food item they wanted “by paying very near their weight in silver.” Still, the effort to respect civilian property was notable in the first year of the war.

As the war continued, however, and the privation of the Confederate army in particular became more severe, the relationship between citizen and soldier changed. During the Confederate occupation of Frederick in September 1862, merchants were required to keep their shops open so that soldiers could obtain shoes. Confederate troops often paid for the property taken from civilians and shopkeepers with Confederate scrip, which was nearly worthless. Some brokers were only giving thirty cents on the dollar in exchange. Many of the shopkeepers tried to close their stores and hide their valuables rather than accept the Confederate money. By 1864, the relationship between the citizens of mid-Maryland and Confederate soldiers grew even more strained. During the Confederate invasion led by Maj. Gen. Jubal Early, Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht reported: “The robbing of horses about the county was general. Some estimate the value of the horses stolen at a million of dollars in the county.

The soldiers stole from the farmers money, meat, chickens, cattle, sheep, & anything that came their way. These are awful times.” The economic hardships of living on a war front were very real to those on the border.

Union soldiers reacted much the same way when they crossed the Potomac. There were many pro-Union residents in Jefferson and Loudon Counties, and Federal troops through the first half of the war kept marauding to a minimum. As the war turned uglier in 1864, however, Union policy became more severe, and the burning of homes and destruction of crops became more frequent. One victim, whose home near Shepherdstown was burned, vented her anger on the responsible Union general: “Were it possible for human lips to raise your name heavenward, Angels would thrust the foul thing back again, and demons claim their own.”

Individual soldiers occasionally indulged in alcohol, and tensions resulted that spilled over to the civilian community. The local provost marshal prohibited civilians from selling intoxicating beverages to soldiers. Drinking establishments were shut down if they violated the order. Liquor was confiscated from grocery stores and saloons, often multiple times.Private citizens who dealt liquor to soldiers also had their alcohol confiscated, and, along with proprietors, faced fines and imprisonment for disregarding the prohibition. In one case, a citizen was forced to stand on the street corner with a sign around his neck that said “I buy whiskey for soldiers.” Since whiskey and brandy were valued for medicinal purposes, contraband liquor seized by the provost marshal was often donated to the hospitals.

The presence of armies in their midst created situations for civilians and soldiers that on occasion ended fatally. Local newspapers reported instances of civilians being shot by guards or pickets, or dying in fights with soldiers. The Hagerstown Herald of Freedom and Torchlight gave an account of a tragic case of mistaken identity in Indian Spring, Maryland, where a local man mistook a Union soldier for a barkeeper who had refused him a drink in a public house, and shot him.

Also affecting the local citizenry were the camp followers that accompanied both armies of the Civil War. Long after the Battle of Antietam, a woman who had been a young girl in Shepherdstown recalled: “What we feared most were the stragglers and hangers-on and nondescripts, that circle ‘round any army, like the great buzzards we shuddered to see wheeling silently over us.” Some of these camp followers tried to pass themselves off as soldiers; their main purpose was really stealing horses and other items from the locals.

The issue of loyalty continued throughout the war, and would often surface when the soldiers were present or immediately after their departure. When the Confederate army moved on after incursions into the region, it left in its wake civilians who would be charged with disloyalty. Some of these charges were based on real acts of treason, while others were for imagined offenses. Civilians suspected of helping the Confederates were brought before the provost marshal and asked to take the Oath of Allegiance to the United States. If they refused, they were imprisoned locally or sent to larger prisons, like Fort McHenry in Baltimore. On August 26, 1863 in Westminster, Dr. J. W. Hering received an order to report to the local provost marshal. Instead, Hering chose to make house calls for his patients. He, and his wife, were arrested that evening and brought before the provost marshal. “And so our party stepped up to the bar,” he wrote, indignant at this situation, “and went through the humiliating farce of swearing allegiance that neither of us have even violated.”

Other military restrictions and requirements curtailed the civil liberties of mid-Marylanders. In Union-occupied towns throughout mid-Maryland, those who wished to travel had to have a pass from the provost marshal to show that they had taken the Oath of Allegiance. Frequently, property of Confederate sympathizers, and those in the region who had chosen to enlist in the Confederate army, was burned or confiscated and sold. Later in the war, known Confederate sympathizers were exiled to the South.

Similar treatment befell pro-Union citizens in Loudon County in Virginia. As early as August 1861 the Confederate Congress issued the Alien Enemies Act, which required male citizens with the Confederacy to swear allegiance to the Confederate States of America within forty days or face deportation. Throughout the war, several Unionists in Loudon County were arrested and sent to Richmond for imprisonment.

Spies were a major concern in some communities, especially in border regions where there were divided loyalties. In July 1863 a spy named William Richardson was captured in Frederick with documents pertaining to the fortifications around Baltimore and the number of troops in the area. Upon confessing, Richardson was tried, condemned, and executed by hanging. His body was left suspended from the tree for four days, and many citizens came by to see the corpse and even take pieces of his clothing as relics. The fate of William Richardson may have caused some would-be spies to be cautious, but efforts by Confederate sympathizers to aid the Confederate cause by either passing information or passing goods continued throughout the war. In February 1863, three Frederick merchants were arrested for smuggling contraband goods to the rebels. Women were not above suspicion: on April 8, 1863, the Frederick Examiner reported that Miss Teresa Jamison was arrested for being unable to explain the disappearance of two Confederate prisoners of war from her boarding house.

In addition to spies, the border area of mid-Maryland collected refugees during the war. After the war began in 1861, many citizens of Berkeley County, Virginia maintained a strong attachment to the Union. When Confederate troops came to the region to enroll men into companies, many of these people fled across the Potomac to Williamsport, Hancock, Hagerstown, and Clear Spring rather than serve in the Southern ranks. One newspaper estimated that about two hundred refugees from Virginia were living amongst friends and relatives in Hagerstown and Williamsport.

On occasion the presence of the army was beneficial to the citizens because it provided employment. Hospitals often hired local women as laundresses and matrons, and these women tended to come from the working classes or, in some cases, were or had been slaves. Vendors who took the oath of office, a practice initiated to exclude Confederate sympathizers, were permitted to sell their wares in the army camps.

Families Divided, Families United

Border regions, including that of mid-Maryland, were replete with families which found themselves with conflicting opinions about how to respond to the sectional crisis and the war. They argued over slavery and secession, and they struggled with opposing loyalties. The issues pierced some families to the core and the result was the painful reality, as well as the powerful metaphor, of “brother against brother.” Familial divisions were evident both in displays of allegiance on the home front and in service in one of the armies.

The Shriver family, with family members living across central and western Maryland, struggled with conflicting loyalties. Of those Shrivers from Frederick and Carroll counties, eight served in the Confederate army and six in the Union army. Louis E. Shriver of Carroll County wrote that four of his cousins fought for the Confederacy, while his own brother served the Union. The result was, predictably, familial tension: “Our two families lived close together and although we continued to visit back and forth, social intercourse was always strained and often resulted inunhappy arguments.”

The Baer family of Middletown was similarly a “house divided.” Jacob Baer was a doctor who briefly served as a medical examiner for the Union army. He had two sons, both also doctors. One son, Charles J. Baer, remained in the Middletown Valley and offered his services as a private physician when field hospitals were set up in the area. The other son, Caleb Dorsey Baer, joined the Confederacy in June 1861 as a surgeon and served with two units of the Missouri infantry until his August 1863 death in Helena, Arkansas, while in charge of a hospital.

Some siblings were on opposing sides in the same battle. Three sons of William Robertson, formerly of Hagerstown, fought at the Battle of Winchester, two in the Union army and the third son in the Confederate army. In another case, John Heck belonged to the Maryland First Potomac Home Brigade throughout the war, while his brother Jacob Heck served with a Maryland unit in the Confederate army. They fought against each other at South Mountain; after the battle both went home to Boonsboro where they had breakfast and visited with their family. They then left to fight on opposing sides in the Battle of Antietam. The brothers both survived, and reconciled after the war.

In addition to tearing families apart, the war occasionally created new families. Marriages between local women and men who otherwise would never have come to this area—soldiers, doctors, hospital stewards—were not uncommon. A Confederate doctor who remained with his wounded soldiers in Boonsboro after the battle would return to the area in 1865 and marry a local woman, Helen Jeanette Smith. Frederick resident Clementine Baker nursed Captain Chauncey Harris of the 14th New Jersey back to health from wounds suffered at the Battle of Monocacy, and later married him. A young soldier who fought at Monocacy died in the home of the Frederick widow who took care of him; his father would marry that widow.

Like families, religious congregations sometimes found themselves divided by their loyalties. The Reverend John B. Ross, pastor of the Presbyterian Church in Frederick, resigned in November 1862 over dissension in the pro-Union congregation caused by his support of the Confederacy. The Reverend Charles Seymour, a strong Unionist, was rector of Frederick’s Protestant Episcopal Church at the beginning of the war, but resigned in July 1862 because of political differences with some of his congregation.

Armies and Civilians

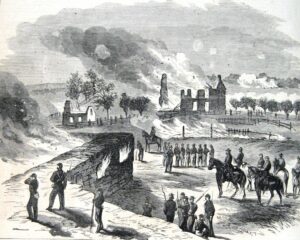

Armies had an immense impact on the communities and surrounding areas through which they marched and in which they camped and fought. They commandeered livestock, flour, grain, fruit, vegetables and other goods from civilians in order to supply the troops. They fought in, and destroyed, fields planted with crops. They took over homes and churches, they destroyed transportation lines, and they left diseases behind. Their presence caused shortages, which caused severe wartime inflation.

The Antietam and Gettysburg campaigns were particularly hard on those engaged in agriculture in the area. Many of the famers near Sharpsburg, Maryland lost their entire crop in September 1862 when fighting took place in their fields during the Battle of Antietam. This left civilians with little to carry them through the winter.During the Gettysburg Campaign of 1863, a Georgia brigade foraging in the vicinity of Funkstown, Maryland, seized enormous amounts of food – 5,124 pounds of corn, 12,400 pounds of hay, and 1,181 pounds of bran – from local farmers. Armies also commandeered horses, sometimes taking them right out of their harnesses while working in the fields or at the threshers. Farmers depended on these horses for their livelihood, and most attempts at retrieving them failed. Some farming communities were left without a single horse. Townspeople and livery stables also lost carriage horses to the soldiers.

An army’s effect on the land could last for years. During the Battle of Gettysburg, one observer noted: “every hill and dale was covered with wagons in number perhaps five thousand. From seven to eight times as many mules and horses fill every pasture and meadow as far as the eye can reach ….” Once-fertile fields were compacted due to the movements of troops, animals, and vehicles, and would no longer bear crops. Fence rails, which soldiers took for cooking fires, had to be rebuilt before livestock could be replaced. Even farmers whose land had been spared from the worst trampling were in need of horses to plow the fields. And plowing was made difficult because soldiers’ graves dotted the landscape, many of them unmarked. Years after the war, farmers continued to uncover bodies while plowing.

Families whose homes were located near battlefields often lost everything. The homes themselves became officers’ quarters or hospitals, while the families’ clothing, shoes, blankets, and linens were taken to supply the soldiers. Tillie Pierce Alleman, a young girl in Gettysburg in July 1863, reported that the first Confederates in town took “horses, clothing, anything and almost everything they could conveniently carry.”

During the Antietam campaign, pillage by Union troops was more remarkable than that by Confederate soldiers. A member of General McClellan’s staff reluctantly concluded that the Confederates had behaved “better than ours will do, I fear.” Officers gave orders prohibiting the plundering of local supplies, but they were often ignored:

Cagey officers pointed at livestock and gave orders forbidding “taking one” pig or sheep – whereby cheerful volunteers quickly corralled two or more. Other Union officers, when asked for permission to use fence rails for campfires, replied, “Just take the top rail” – a juncture repeated until the fence was gone.

Towns themselves were severely affected by occupying armies. Several years into the war, some Frederick residents left the area because of “too much fuss here on account of war.” Harpers Ferry, which changed hands many times early in the war, was nearly abandoned by its citizens. Only after the Union army established a secure supply base in the town did some of its residents return. The town of Williamsport suffered in another way when, after the Battle of Gettysburg, the entire Confederate army occupied the town for ten days while waiting for the Potomac to fall. Vast herds of livestock that had been seized from the countryside were corralled between the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Potomac River. The accumulated animal waste and remains of slaughtered livestock, worsened by a week of heavy rain, turned parts of the town into putrid swampland. One soldier described Williamsport after the army left: “The houses are riddled and almost all deserted and the country for a mile around is feted with beef offal and dead horses.”

Disease often followed an army, and it did not spare civilians who were exposed. Many whose homes were used as field hospitals suffered especially hard. After the Battle of Antietam, typhoid fever spread from the troops to the civilians around Sharpsburg. Samuel Michael, a Sharpsburg resident whose house was used as a field hospital, lost two family members to the disease. Epidemics of diphtheria and scarlet fever also raged through the Middletown Valley in the post-battle days of October 1862.

Local transportation lines were prime targets, and Confederate troops disabled them in this region whenever they could. Before they evacuated Harpers Ferry in June 1861, Confederate soldiers rendered inoperative both the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. This affected local citizens in numerous ways. Farmers and merchants were unable to forward goods to market, citizens and businesses experienced shortages of products that were shipped in from other regions, and those who worked on the railroad and canal lost jobs. The Hagerstown Herald of Freedom and Torch Light complained that “[The Confederates] have … deprived these people of all means of livelihood.”

The armies did more than commandeer supplies, trample fields, bring disease to civilians, and destroy transportation lines. During their 1864 campaign into Maryland, the Confederates demanded ransoms from local towns under the threat of the torch. Levies of property and cash were imposed upon the citizens of Hagerstown, Middletown and Frederick, which were successfully raised from the civilian population, merchants and banks. Citizens of Chambersburg, Pa., were not as successful in raising the money ransom demanded, and the town was burned.

The demands of the armies to feed and supply their soldiers, along with the destruction of crops and transportation facilities, created shortages that caused prices to rise throughout the region. This wartime inflation had a serious impact on the local economy. A month after the Battle of Antietam, a Hagerstown newspaper wrote: “In consequence of the immense accession of soldiers and other strangers to our population, the prices of everything which enters into the consumption of a family have greatly advanced. Country produce of every description, as well as Groceries and Dry Goods, are sold at prices which have never before prevailed here, and which render living a very expensive affair.” In addition, because many young men were in the army and others displaced from the region because of the war, labor was scarce and high-priced.

Civilians expected to be reimbursed for their losses by the Federal government; most claims, however, took years to process and usually reimbursement was much less than requested. Temporary commissions were established during the war to consider claims for damage caused by Union troops, but many citizens did not receive any remuneration until long after the war. And since the Federal government only paid for losses caused by their own army, many people whose farms and belongings were damaged or taken by the Confederate army had no way to recoup their losses. Some farms failed, and families, like the Prys of Keedysville, chose to leave the area after the war to seek better fortunes out west.

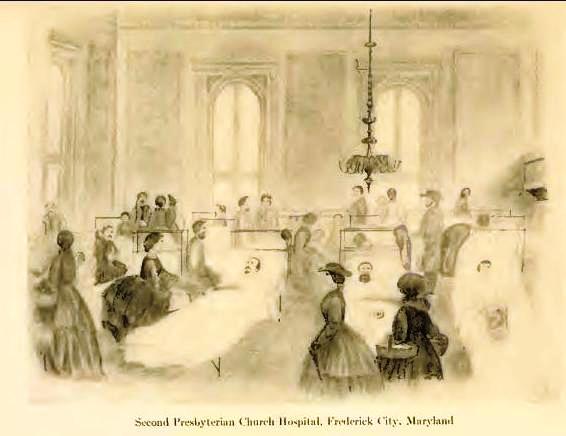

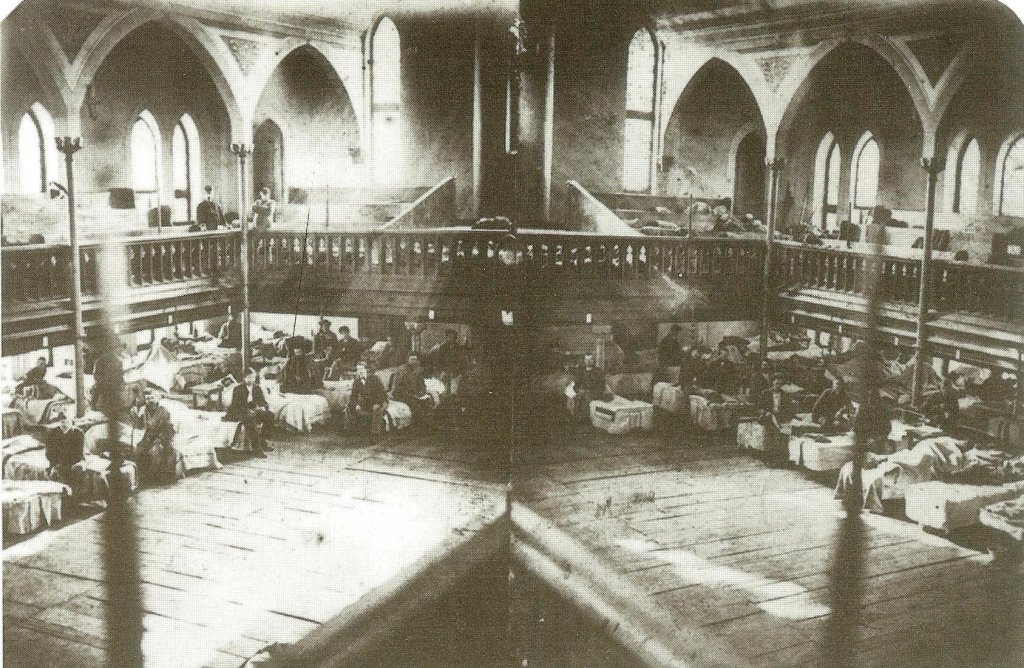

Caring for the Wounded

With the extent of fighting taking place in the mid-Maryland region, communities in this area were called upon to provide help in treating the wounded and sick soldiers from both armies. Towns were often full of soldiers needing medical attention – after the battles of South Mountain and Antietam, the number of wounded soldiers in the city of Frederick equaled the number of residents. Since there was no established system of military hospitals before the Civil War broke out, the plan for the evacuation and care of the wounded evolved as the war progressed. A network of temporary field hospitals was set up near the battles and more permanent pavilion, or general, hospitals were established away from the fighting. Division or corps hospitals, usually tent hospitals, were more mobile and followed the troops. Frederick was designated as the site of a permanent pavilion hospital, with churches and other public and private buildings enlisted for additional hospital space.

Field hospitals were set up in the areas immediately adjacent to the battles, and most nearby towns hosted field hospitals in both public and private buildings. When the Confederate army retreated across the Potomac River after the Battle of Antietam, the wounded that could be transported traveled with them. Those that could not be moved were left in the field hospitals near Sharpsburg and were cared for by the Union Medical Department. The town of Sharpsburg was nearly overwhelmed by 10,000 wounded soldiers from both sides, with nearly every available building used to shelter them.

Conditions at these hospitals varied due to the nature of the facilities, the availability of supplies, and the ability of the townspeople to provide assistance. In her travels to assist the soldiers of Maine in the fall of 1862, Isabella Fogg noted that while Middletown hospitals were “very comfortable” and the wounded men “happy,” the conditions in Keedysville were “a painful contrast.” Hospitals closer to the battlefield, like the one at Keedysville, bore the brunt of caring for the most severely wounded men and had greater demands made on the civilians and the available supplies.

Residents often had no voice in the decision to turn their homes and barns into hospitals. Samuel Michael of Sharpsburg noted on November 27, 1862 that “they forced a hospital on our house. Kate and Mother fought them hard.” He also wrote: “The hospital was continued in our parlor for several weeks. I do not know how many have died in it. They have left it now. It looks like a hog pen.” Sometimes residents were keen on having their homes identified as hospitals, as they believed that would afford them some protection. Just after the Battle of Antietam, local resident Mary Bedinger of Shepherdstown, Virginia, recalled: “Some one [in Shepherdstown] suggested that yellow was the hospital color, and immediately everybody who could lay hands upon a yellow rag hoisted it over the house. The whole town was a hospital; there was scarcely a building that could not with truth seek protection under that plea.”

The sick and wounded Confederates left behind received the same treatment as their Union counterparts, and usually side by side. Both Medical Departments operated under the belief, articulated by one soldier, that “Humanity teaches that a wounded and prostrate foe is no longer an enemy.” Even many Confederate sympathizers remarked on how well the Southern wounded were treated. Several Confederate soldiers wrote a note of gratitude that was published in the Frederick Examiner, rendering their “sincere thanks to the Union Ladies and citizens of Frederick City, Md for the kind treatment and attention shown us, while we were in the above hospital [Methodist Episcopal Church Hospital].” These soldiers also thanked the surgeon in charge, “who done all in his power for our comfort and good.” An exception to this policy occurred when a group of women who supported the South set up a hospital that would only treat Confederate soldiers. The reaction to this was notable: one local Frederick paper bemoaned the separate hospital, since “it gives greater license to this sectional discrimination and an opportunity of cultivating a baneful rivalry.”

Civilians provided medical care for soldiers in a variety of ways. Local doctors often offered their services to the wounded. A Dr. Hering recalled the scene in Westminster after Confederate General Jeb Stuart’s cavalry clashed with Delaware cavalry on June 29, 1863: “The dead and the wounded were lying in the street and we were in the midst of war indeed. Stuart’s column was then beginning to pass through . . . . The bodies of the dead were taken away and, with other doctors of the town, I set myself looking after the wounded.” Women and children were also engaged in caring for the soldiers. They made bandages, prepared and distributed food, supplied clothing, hauled water, collected money for the hospital fund, and even helped surgeons with operations. “Women bandaged and bathed, with a devotion that went far to make up for their inexperience,” recalled one observer. “[They] helped, holding the instruments and the basins, trying to soothe or strengthen. They stood to their work nobly….” Children did noble work as well. When the farm ten year old Tillie Pierce was sent to in order to escape the pending battle at Gettysburg became a field hospital, Tillie helped with the care of the wounded soldiers who were placed in the house, barn, and orchards.

Ann Schaeffer of Frederick noted the irony inherent in the idea of military hospitals: “I could not help thinking how ridiculous our world must appear to superior intelligences—our incurring so much trouble, expense and suffering to maim and murder each other and after accomplishing this object, laying the poor creatures side by side – endeavoring to relieve their pain and save their lives.”