Discover The Story

Civil War Stories

The Great Escape

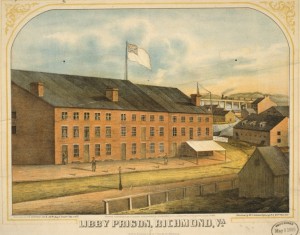

In March of 1862, in response to the growing number of Union prisoners of war, Confederate authorities converted an old tobacco factory in Richmond, VA, into Libby Prison. In June of that year, the facility became an officers-only prison. Libby Prison earned a notorious reputation as a overcrowded, rat-infested hell hole where living conditions were deplorable and disease rampant. By early 1864, even Confederate officials realized that conditions were ripe for a prisoner revolt, and they began planning to transfer Libby’s inmates to other prisons further south.  Before the exodus began, however, one of the most famous prison escapes of the Civil War occurred at Libby Prison. At the center of the escape plot was an African American teamster from Frederick, Maryland named Robert Ford.

Before the exodus began, however, one of the most famous prison escapes of the Civil War occurred at Libby Prison. At the center of the escape plot was an African American teamster from Frederick, Maryland named Robert Ford.

Little is known about Robert Ford. In 1860, he was 32 years old and living in Frederick City with Martha, aged 20, and William, 2 years old. In the Frederick City Directory for 1859-60, Robert was listed as living on East Church Street. On May 1, 1862, Ford started work as a teamster for the local Union Army’s quartermaster. His employment did not last long however, as he was captured on May 22 while accompanying the army of Union General Nathaniel Banks in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Ford was sent to Libby Prison where he became the hostler (stableman) for the prison’s second-in-command, Dick Turner. Ford therefore had more freedom of movement than other prisoners.

Throughout the war, a secret network of Union loyalists operated in Richmond, sending information through Confederate lines to Union contacts and aiding Union prisoners in the city’s prisons as best they could. Several of these agents were women considered part of Richmond’s highest circles of society, such as Elizabeth Van Lew and Abigail Green. Green in particular sent her African American servants to make contact with African Americans working within the prisons. Robert Ford became the main contact in Libby Prison. According to one historian, Ford “was the vital link between the prisoners and the outside world…..”

In early 1864, several Union officers imprisoned in Libby hatched a scheme to tunnel their way out of the prison. Ford was “instrumental” in the planning of the escape. He relayed messages back and forth between the officers in Libby and Green and Van Lew on the outside. He used twine to measure the distance from the prison wall to a point across the street in a fenced lot where the tunnelers could safely surface. He also provided the officers detailed directions and information on where they should go for safe haven after the escape, and he alerted Green when the escape was to take place. On the evening of February 9, 1864, and through the night, 109 Union prisoners crawled through the tunnel to freedom. They fanned out through the city to safe houses, and were assisted in the coming days by both the underground network of Union loyalists in Richmond and by many African Americans in the region, slave and free, who guided them once they were outside the city. Fifty-nine of the escapees reached Union lines; 48 were recaptured and 2 drowned in their escape attempt.

Ford was severely punished after the escape. Dick Turner suspected him of helping the officers escape, so he gave Ford 500 lashes in a beating that almost killed him. According to Abby Green, in later testimony about the incident, Ford endured the whipping “without ever betraying certain other persons who had aided in concealing said prisoners after their escape.”

Ford never fully recovered from his flogging. He was “helpless” for six weeks after the incident, but in July 1864, he managed to escape Libby himself and make his way to Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, the details of his escape are not known.

For his heroic actions, the U.S. Congress passed a bill in 1868 giving Ford $814 (the pay he would have earned as an army teamster during his incarceration), and acknowledging that he “was very serviceable to the Union prisoners, affording them information, and aiding their escape from prison…..” Ford also secured employment as a laborer in the Treasury Department. After Ford died in April 1869, partly due to his beating at Libby, a Congressman from Indiana wrote a tribute to Ford, saying that “the nation owes him a debt of gratitude.”

This essay was contributed by Dean Herrin Ph.D., National Park Service Historian and Co-Coordinator, Catoctin Center for regional studies.